Data centers need more power (reprise)

Daily Data: The hype appears to be real, and investors are placing their bets

[A little late today, because scheduled delivery failed, and then I decided to add more parts. I may republish this one tonight.]

In today’s dispatch, Random Walk mixes charts with actual secondhand knowledge from a real-live data center professional.

AI needs more data centers and data centers need more power

it will take time, money, and planning . . . an entire supply chain that was sleepy for years is now go-go-go, and big investments are being made on companies no one had ever heard of, until recently

where will the power come from? no one is really sure. maybe China can help.

where will the skill come from? no one is really sure about that either.

good news on the electrification of everything (and bad news for the green new deal)

👉👉👉Reminder to sign up for the Weekly Recap only, if daily emails is too much. Find me on twitter, for more fun. Data centers need more power (reprise)

It has rapidly become consensus that the demand for energy is gonna be off the hook.

The precipitating factor is AI. AI is in high demand, AI requires lots of compute, and compute requires lots of energy.

Of course, you can’t just plug your GPU (assuming you can get one) into an outlet. The energy-sucking GPUs live in data centers, and it’s the data centers that suck energy from the grid. And we don’t have enough of those, either.

Anyways, Random Walk talked to a data center professional to figure out if there was steak to this sizzle, and yeah, it turns out there is.1

Couldn’t build more data centers if we wanted to (reprise)

I don’t understand the big deal. We have lots of data centers. Why can’t we just send more power to the data centers we have.

Not that simple. Not all data centers are built or equipped to manage the energy throughput that the hyperscalers (e.g., Microsoft, Google, Meta, Amazon, etc.) are now saying they’re going to need to power all that compute they’re expecting to sell.

OK, so build more data centers. Or refurbish them.

Again, not that simple.

Certainly more data centers are being built and refurbished (and every part of that value chain, including everything and everybody involved in the business of making, fixing, or refurbishing data centers is in hot demand).

Oh you make cooling components for data centers? We love you now:

Vertiv has been around for almost a decade, but no one had ever heard of it until ChatGPT rolled out.

But making more data centers (a) it takes time; and more importantly, (b) data centers need to do more than manage the heightened energy load, they need to source it. There’s no use in a rocket with no jet fuel.

So call the utility.

Good thought. But the thing about utilities is that they are (often) slow-moving, carefully managed state bureaucracies that do not (or cannot) respond quickly or well to rapidly changing demand.

A data center can’t just say “hey, we’re going to need 2-3X as much energy this year.” This stuff is managed, budgeted, planned, etc.

Plus, it’s not like utilities just have extra power plants (or latent power generation) lying around. If the grid needs more energy, then it’s likely that more generating needs to be built, and building energy-generating infrastructure also takes time, and money, and planning.

OK, but there’s a lot of money to be made. Surely the utilities can kick things into a higher gear.

Probably, but in fairness to state utilities, demand for energy has been flat for a long time.

In further fairness to utilities, they’ve been instructed by the federal government to avoid and otherwise decommission anything resembling a cheap and reliable energy source, like LNG or nuclear. So, just “building more power generation” introduces its own host of questions, like which kinds? And will the government ask me to shut it down in a few years? There’s lots of uncertainty and risk, and state utilities do not like those things.

This is going to take a while, isn’t it.

Yes!

Just to give you a sense, even when data centers can get into the “interconnection queue” (i.e. get an energy commitment from the utility) servicing often won’t start until 2030.

But demand is so intense (and supply is so scarce), that hyperscalers are signing big contracts now anyways—again, based on energy commitments that (in some cases) can’t/won’t be fulfilled until 2030. It’s like buying a pack of very expensive plane tickets for a whole bunch of trips you expect to take five years from now .

So basically you’re saying that a few months of screwing around with a firehose of statistically commonplace text is setting in motion a daisy chain of huge capital expenditures based on an unknown set of contingencies expected to play out over the next half-decade (at a minimum)?

Pretty much. Investment is exciting like that.

Well, hopefully nothing changes between now and then.

Probably lots will change. And lots of good things too . . . like increased efficiency, better/smarter transmission, alternative power sources. We wanted innovation in atoms instead of bits, and software (ironically enough) is going to give it to us (hopefully).

But in the meantime, we need more power, and AI is going to run out of power, before we run out things to do with AI.

That’s the thought, at least.

So much power, but where does it come from?

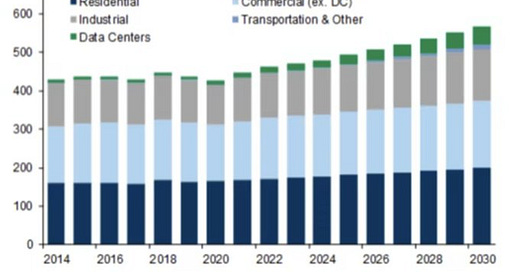

Look how much power data centers are going to need:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Random Walk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.