It's not 'how many?' but 'who?'

4 thinks and 5 reads on stuff that matters that you might have missed. Stealth Stimuli; Death of Cable; Not how many, but who; & Bonus Season. Plus AI, suburbs, transit, investorGPT, and more.

Random Walk here to keep your information mix F-R-E-S-H.

The thinks:

Stealth stimulus or nah?

Death of Cable! Long Live Cable!

It’s not “how many?” it’s “who”

What to expect when you’re expecting bonuses

The reads:

AI’s legal troubles

Fitch is Right

7 Transit Projects Real Estate Investors Need to Know

Investors using ChatGPT to sift through “Disclosure Bloat.”

The Suburbs Won. Get over it.

Have a nice weekend everyone. Please do subscribe, and if you’d like to sign up for a paid subscription, but can’t figure out how, please just reply to the email.

Finally, if you haven’t already done so, the Substack app is a much better way to read RW than email:

Random Walk Thinks

No Stealth Stimulus?

RW previously alluded to the “stealth” fiscal stimulus, i.e. the fact that while the Fed is trying to “destroy demand,” the U.S. Treasury is as demanding as ever. It’s part of the dualling Wars on Inflation and Deflation. When contraction meets expansion, well, you know, nobody really wins. The point was (a) if the strength of the economy is just money printing again, then we should know by now that that strength is illusory; and (b) it’s unfortunate that everyone is working so hard to paddle in opposite directions.

Anyways, Matthew Klein (

) has made the contra-RW argument that there is no stealth fiscal stimulus. Good. Teach me why I’m wrong.The crux of the argument is that only certain kinds of government payments are stimulative, and those payments are not unusually high:1

The federal government pumps money into the economy when it pays its employees, buys consumables such as ammunition or consulting services, makes investments such as aircraft carriers or scientific research, and when it provides more transfer income to households and businesses than it takes away with taxes. The federal government also provides substantial financial support to state and local governments, which in turn pay employees, buy goods and services, make investments (mostly in physical infrastructure), and distribute transfers . . . It turns out that the categories of federal spending and taxation that most obviously correspond to changes in private sector spending power for goods and services have not moved relative to GDP over the past year . . . [t]he entire increase in the deficit has been a function of higher interest rates and lower capital gains tax receipts.

To summarize, direct “stimulative” transfers have gone up, but not unusually so. Non-stimulative transfers, like interest payments, have gone through the roof, but those are non-stimulative (says Klein).

I admire the thoughtfulness of the analysis, but RW doesn’t find it persuasive or comforting.

First, even Klein agrees that stimulative payments are in fact growing. That they are not growing unusually quickly is neither here nor there. ‘You see, the gap between costs and revenues (i.e. the deficit) is getting wider and wider, just like it did before,’ says Klein:2

That is supposed to give us comfort (and more mean reversion), but it’s still getting wider and wider, which means it’s stimulative, even if not unusually so (and again, the Fed’s point is to put the kibosh on stimulation, not “keep stimulation at its prepandemic growth rate.”).

Second, I’m not nearly as sure that $500B extra in annual interest payments to bond holders is as neutral as Klein seems to think. $500B in extra dollars is a lot of dollars.

Klein points out that ~40% of our debt is held by foreigners (but also points out that that number is down substantially from the 70% peak, back in ‘05 a few years ago). OK, but that’s still ~60% of that $500B staying right here (and possibly more, considering we bought an even great share of the most recent vintages).

More importantly, Klein just sort of asserts “that it’s extremely unlikely [recipients will] use the incremental income from higher yields to finance higher spending on goods and services.” Why he believes that, I’m not sure, but I know plenty of people and companies who are rocking out to ~5% yields on their deposits. Again, $500B (and growing) is a lot of money.

Third, and this one may be because I’m missing something, but the IRA and CHIPS Acts are definitely stimulative, and have led to a massive increase in construction spending on semiconductors and tesla batteries, and things. Perhaps the actual stimulus is a relative drop in the bucket, but the case needs to be made.

Stepping back, the bigger issue here is that healthcare consumption (and pensions) are a huge chunk of the Treasury’s annual bill. These are only getting bigger, and there doesn’t appear to be anything the Fed can do to “destroy” that demand. To the contrary, higher rates just mean more interest payments (and more borrowing) and therefore even more expansion. While ordinary people respond to higher borrowing costs by borrowing and spending less (which is deflationary), Treasury hasn’t flinched. It marches to the beat of its own (inflationary) drum.

Death of cable! Long live cable

RW has variously observed (with others) the slow death of cable, and Nielsen data once again confirms that cable does appear to be dying slowly:

I call attention to the trend because (a) it’s a new pattern of life and living, and RW likes those; and (b) not all that long ago, Cable was an unstoppable cartel whose predation could only be curbed by the plucky heroics of the largest syndicate of all, the Federal Trade Commission. RW likes it when definitely true things become false.

Obviously the FTC and its champions were almost certainly wrong about cable (just like they were wrong about Microsoft, and just like they’re wrong about Google and Amazon), but that’s not really the fun part.

The fun part is the particular way in which they were wrong. I’m generalizing a bit, but the bad thing that Cable companies were supposedly doing is called “bundling” (i.e. creating packages of channels, rather than offering them a la carte).

To the pitchforks and regulate crowd, this practice was a devious way of forcing consumers to buy more than what they wanted. More enlightened people tried to explain that a la carte would eventually cost more for more people than bundling, and bundling was in fact an optimal way of delivering a basket of content, while mediating the varying tastes for the items in that basket. Bundling is also especially necessary to support the existence of relatively niche content. Lots of people paying a little for content they sort of want, makes it possible to deliver content that only a small number of people really want (at a price they can actually pay).

Ben Thompson says this is the definitive piece on the economics of bundling, and I believe him:3

You see. The same bundle gives two very different people exactly what they want at a discount. Magics.

Anyways, back to the story.

Fast-forward a few decades, and streaming has gained substantial market share at cable’s expense by unbundling or rebundling certain content. Hooray for the consumer! Cheaper a la carte offerings! Cut the chords, cable is terrible! We didn’t need the FTC because innovation does it’s thing, but at least the FTC is vindicated about who the baddies were!

Nope. No vindication in the slightest.

Because here’s the thing: as cable companies lose customers, the economics of bundling make less sense. Scale is part of how it works, especially for zero-marginal cost goods, like content (where all the costs are in making it, but once it’s made, it replicates endlessly). The less bundled subscription revenue there is, the less there is to spread out amongst the various studios and networks in the bundle . . . so the studios and networks eventually say “why are we letting streamers take our content for pennies? When customers paid for cable, we got paid. Now when they’re just paying for Netflix, we don’t, so why give our content to Netflix? We’re going to take our best content directly to our most intense fans and make them pay us.” This is a simplification, but you get the idea.

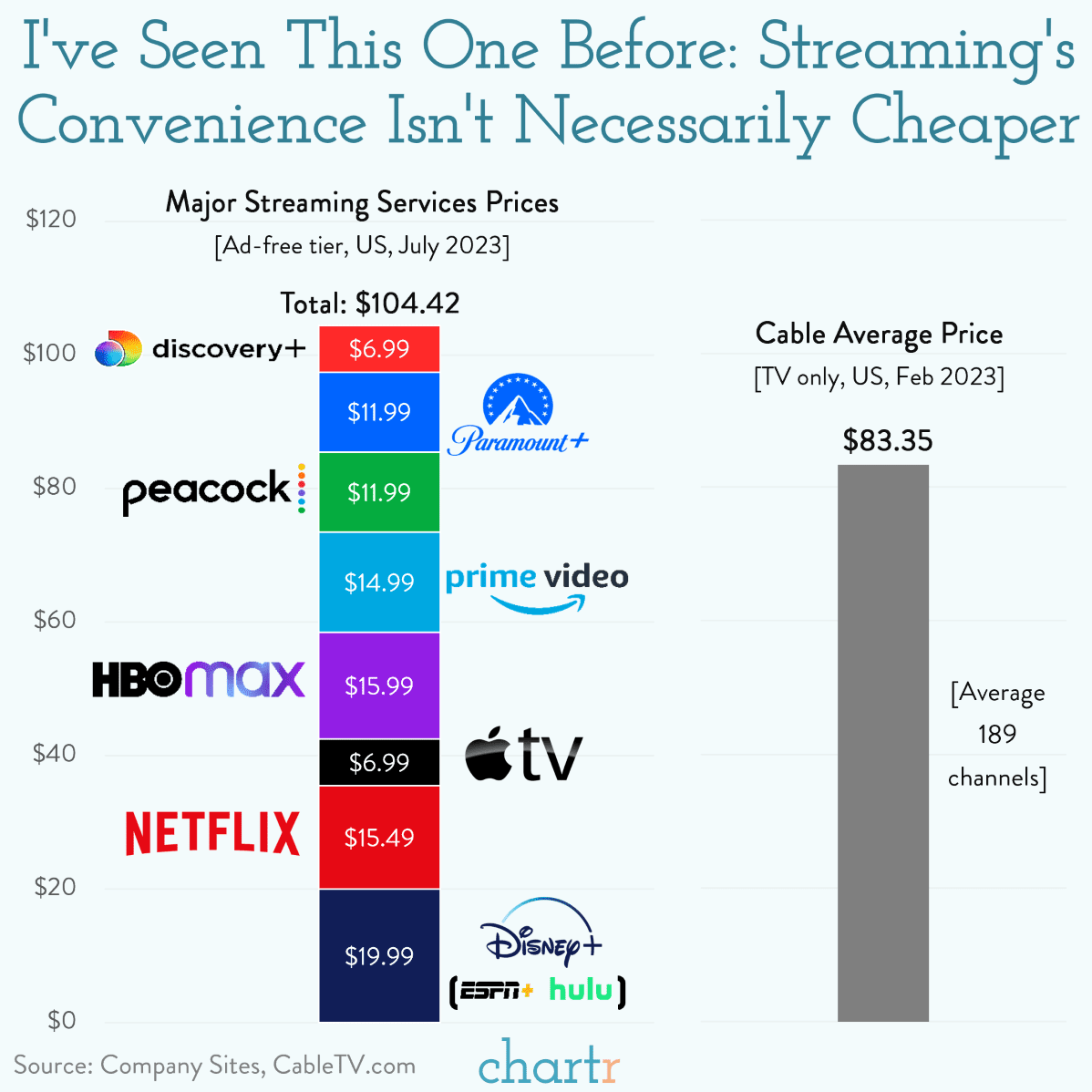

The net result is that we’re right back where we started before bundling: lots of somewhat expensive a la carte subscriptions that now cost more in total than a single bundle:

Cable companies didn’t bundle because their [fake] monopolies empowered them to force goods and services on innocent customers. They bundled because it was better for the consumer, and competition from other cable companies makes you do that sort of thing.4

In terms of the here and now:

If you’re the type of person who kind of likes content from all of these places (which is most people), you’re increasingly worse off.

If you’re one of the few people who just really loves Peacock, well congratulations, you’re in luck.

If you’re the kind of person who has very obscure tastes, well, your stuff just won’t be on TV anymore, it will be on YouTube or something (and maybe that’s for the best).

Why else do I find this notable?

Large scale counterfactuals are generally hard to play out in real life—we rely on econometrics and modeling instead—but in this case, we actually did a real life experiment. “What if there was more a la carte” is a question we used to answer with hypothetical case studies that various paid (and unpaid) experts would proffer. Now we can answer with a reasonable degree of confidence: we end up paying more for less, just like the irredeemably evil cable companies said we would.

Perhaps having a little less content is a good thing, but that’s a separate question.

Not ‘how many?’ but ‘who?’

A Bloomberg editorial made the argument that SF is not the “next Detroit.” I wasn’t aware that people *had* compared SF to Detroit, but sure, despite their troubles, they are pretty different, seeing as an information/tech hub is more diversified than a single-purpose manufacturing one.

Anyway, that’s not why I bring it to your attention. This little chart of “Most Affluent Metros in 1949” is why:

In the simplest sense, the chart is a reminder that things do change and that these changes really do matter. The center of the country was an economic and cultural force, perhaps the dominant one. That dominance did not live out the century, and the subsequent economic and cultural shifts from the middle (Detroit, Cleveland, Milwaukee, etc.) to the coasts is a palpable feature of our today (and the last few decades).

RW has variously made the argument that another shift is underway to the New Centers of Attention, in the South and Mountain regions. Skeptics rightly point out that “boom towns” (e.g. new “Detroits” or manufacturing hubs) are less enduring than the sort of industry agnostic cultural capital accumulated by the Acela Corridor and PacWest. Just because an EV plant opens in TN and a bunch of people move there, doesn’t mean TN is in-it-to-win-it for the long haul. Point taken.

But there’s a counterpoint: it’s not just construction workers who are making the move. The biggest winners of wealthy in-migration ($200K+) are also the New Centers of Attention:

That’s the kind of social capital that packs a bit more cultural punch. It’s also evidence (I would guess) of a more diversified, amenitized and mature economy—these aren’t just single-use company towns.

That wealthy people are moving (and staying) to the New Centers of Attention is also why I find headlines like these--wherein Miami is already in a doom loop--to be unpersuasive:5

Sure, it’s true that people are leaving Miami. But they’re not leaving Miami because it’s an undesirable place to live. To the contrary, they’re leaving because the club is getting increasingly more exclusive and they can’t afford to stay. That’s very different than NYC or SFO where even the wealthiest are getting the hell out of Dodge.6

Compare the household income of incoming Miamites (albeit from 2021):

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Random Walk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.