Power generation is fine. It's transmission that's the problem

We've got 2x as much power waiting to be connected to the grid than in the entire grid itself. So what's the hold up? It's hard to say.

power, power everywhere and not a drop to drink

the bottleneck is in the interconnection queue . . . but why?

costs more than anyone would like

it’s a solar (and storage) problem specifically, and there’s no obvious reason why, but diseconomies of scale, might have something to do with it

👉👉👉Reminder to sign up for the Weekly Recap only, if daily emails is too much. Find me on twitter, for more fun. Power, power, everywhere, and not a drop to drink

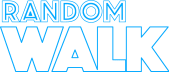

Let’s start with a widely accepted premise that AI and their data centers are going to need more power.

Data centers have already gone from 4% of US grid consumption to 8%, and that’s without AI having much of an impact.

OK, so we need more power. This we know.

Then why not just make it? Drill baby drill. Solar array, solar(?) Doesn’t have the same ring to it, but you get the idea: need energy, make energy, wash-rinse-repeat.

Look, reinforcements are on the way:

So much electric generation growth!

Nope. Not gonna do it. It’s not nearly so simple.

Why? It’s complicated, naturally.

Interconnection purgatory

It turns out that making the power isn’t actually the hard part.

The hard part appears to be connecting the power to the grid.

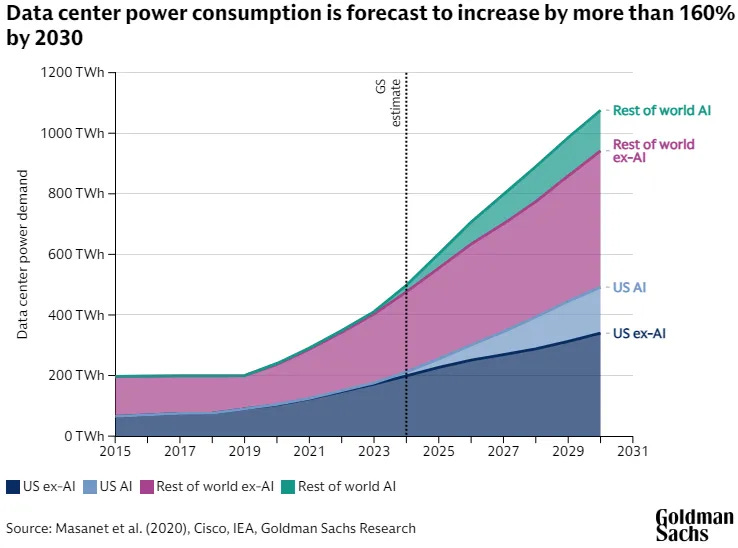

The amount of power capacity that is currently “in queue” has exploded in the last ~5 years:

There is currently ~2X the amount of energy “in queue” (i.e. waiting to be added to the grid) than active energy capacity in the grid itself.

These charts are from the Berkley Lab, and as per the researchers themselves:

This proposed capacity is more than twice the total installed capacity of the US power plant fleet as of the end of 2023 (∼1,280 GW55). Approximately 95% of the capacity in the queues is for solar (1,086 GW), storage (1,028 GW), and wind (366 GW).

The active capacity in these queues represents more capacity than the system could feasibly absorb or that the market demands in the near- to medium-term; this situation is particularly acute in some regions like CAISO [California], where active capacity in queues represents more than six times that region’s installed capacity

Proposed capacity is twice the total of what’s live, as of the end of 2023 (and 6X in California).

So, we appear to have plenty of energy—especially solar energy—but we have an enormous backlog in getting that energy hooked up to the grid.

And why is so much energy stuck in interconnection purgatory?

Well, that’s the billion dollar question, and unfortunately, there is no obvious answer.

First, to clarify, the interconnection queue isn’t a perfect proxy for energy-in-the-waiting (and likely overstates proposed capacity by a lot).

Power-generators often file multiple applications (partly because of the backlog), but also because identifying the least expensive place to connect is part of why the system exists (more on that below). In other words, a would-be generator files multiple applications, and then proceeds (or not) with the best one.

But that limitation aside, let’s just stipulate for a moment that there is a lot of energy-in-waiting, even if we don’t know precisely how much. And that’s bad, considering we all seem to agree that we need that additional energy, a lot.

So, to repeat, why can’t we get all that energy—particularly solar energy—connected to the grid?