Random Walk at Night: Phantom ZIRP

Assumptions that were once true are no longer true, but we feel them just the same

Random Walk at Night tries to make sense of asset prices and wonders whether we got so used to ZIRP we feel like it’s still there.

Editor’s Note: everything reads better in your browser or in the app. The footnotes especially, and Random Walk is really leaning into the footnotes. Plus, if you have the app, you can set delivery to “app only” and then my daily barrage will feel less like a barrage. Unfortunately, substack does not yet have a “Weekly Digest” option, but I’m hectoring them aplenty.

If this email was forwarded to you, please click the shiny blue button:Random Walk at Night

Phantom ZIRP

Random Walk posits the existence of “Phantom ZIRP.”1

Like a phantom limb, Phantom ZIRP is a continued belief in asset prices based on a relationship that no longer exists in a high(er) interest rate world. But because we got so used to it for so long, we continue to believe it’s there (even though it’s not).

This is admittedly an under-baked theory, so consider it more of a trial balloon, but here it goes.

In the ZIRP days, if the economy was fine-to-good, stocks (i.e. equity or assets) went up. When stocks go up, it means the economy is fine-to-good. If the economy is bad, sell your stocks. If people are selling stocks, it means the economy is bad.

ZIRP ended and interest rates went up.

The point of raising interest rates was to “destroy demand,” i.e. make the economy bad(der). Important people (and not important people, like RW) said ‘doom is nigh. If the Fed intends to make the economy bad(der), you should believe them. Money is important and less of it will make life harder.’

Fast-forward ~1.5 years and rates are still high—higher even—but the economy is not bad. It’s OK. It might even be good, depending on how optimistic you feel.

‘The economy is good? Oh, I remember this . . .’

<ENTER PHANTOM ZIRP>

‘If the economy is good, then stocks are good. If stocks are good, then the economy is good.’

Tralalalala and away we go.

You see, it’s the last part that shouldn’t still be true, but people are acting like it is.

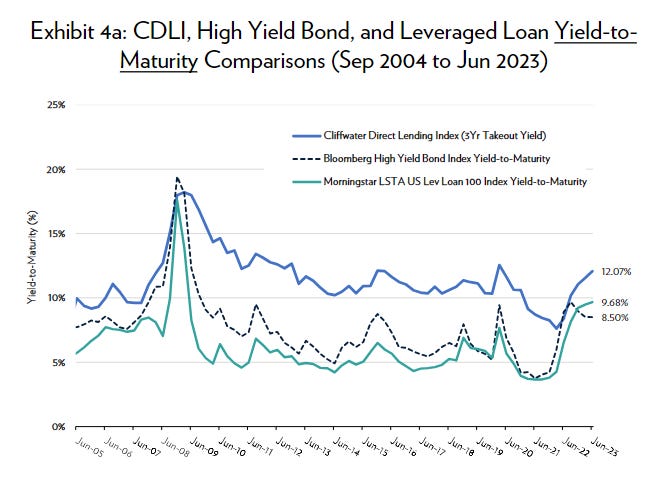

In a high rate environment, even if the economy is good, stocks aren’t necessarily a good investment.2 The reason is simple: you have some pretty good alternatives that are less risky, but still pay pretty well. Take, for example, US 10 Years paying ~5%. And if not that, then corporate bonds or private debt yielding 10%+.

The point is, that in a Post-ZIRP world, if you’re going take equity risk, you better be getting paid for it.

The old median investor logic “economy good, stocks good” just isn’t true anymore.

As per Howard Oaks, it doesn’t matter whether things are good or bad. When rates are high(er), you shift your allocation from assets to lending, equity to debt, stock to bonds, etc. If money is plentiful, you’ll invest it in increasingly speculative ventures. If money is more scarce, then you demand more certainty.

This capital shift happens even if everything else stays exactly the same, including the goodness of the economy. Things that were investable before become uninvestable simply because the floor moved up.

But if the floor stays low and still for a really long time, I suppose one could forget that it’s there or that it matters.3 “Is the economy good or not?” becomes the rule of thumb, even though “is money plentiful or not?” is still a very important question.

Like the old DFW joke:

The old fish swims to the two younger fish and asks “how’s the water?”

The two younger fish just stare blankly. “What the heck is water?”

Interest rates have been so low for so long we’ve forgotten they matter to asset prices.

That’s my speculative armchair psychoanalysis, at least.

Anyways, the result of this Phantom ZIRP is that asset prices stay high(er) than they ought to be. People feel rich because on paper they are rich, but it’s hard to see how those paper gains hold.

Why do I think this?

Well, the first reason is because I’m thinking out-loud and this is an under-baked theory.

The second reason, I guess, is that it just seems like assets are mispriced everywhere and I have a hard time explaining it.

Public equity

Consider the relationship between Nasdaq and the 10year.

If lower risk things (like the 10year) generate higher yields, it should suck money from higher risk things (like Nasdaq). Price and yield should be inversely correlated.

That’s what’s happened before, but not now:

Either Nasdaq investors are wildly overpaying for their risk, or 10year investors are getting the deal of a lifetime, but someone is wrong. Right?

Here’s another cut of basically the same thing, i.e. the equity risk premium:

The extra yield you get for your risky equity investment is . . . 0. More risk, without more reward. How can it be?

It can be if you stop paying attention to the rising floor. The economy is good. Your stocks are good. Interest rates? What are those? Phantom ZIRP abides.

Here’s another one, that’s admittedly less straightforward. The price of bank loans and private loans are starting to converge:

Are loans getting equally risky or is someone not getting paid enough?4

Home equity

And another one, which is a Random Walk favorite, home equity value.