Random Walk at Night: The Marks Are Too Damn High

Private equity says everything is fine and we're also gearing up for a fire sale

Random Walk continues to observe the evolution and (mostly quiet) turmoil in the private capital markets with great interest.

Everything reads better in your browser or in the app. The footnotes especially, and Random Walk is really leaning into the footnotes. Plus, if you have the app, you can set delivery to “app only” and then my daily barrage will feel less like a barrage. Unfortunately, substack does not yet have a “Weekly Digest” option, but I’m hectoring them aplenty.

If this email was forwarded to you, please click the shiny blue button:Random Walk at Night

Private Equity Marks are Too Damn High

I don’t think one can understate the extent to which the rules of the investing game have changed (even though many will try). There is an entire industry and asset class(es) built on a free money spigot, where generally all investments appreciated because there was always more free money.

The majority of the investing skillset was “raise money, deploy capital, repeat.” Making any investment was a “good” investment, so the people who invested the most, invested the best.1

That’s no longer true, of course. The rules have changed, but the bets made under the old regime do not get a reset button. They are now bad bets, or less good bets. Life is tough sometimes.

It is most definitely true, however, that investors are clever people, and they will adapt to the new rules (or try to). If now they have to pick good companies, rather than just more companies, there’s reason to believe they can make that change. Likewise, the fact that capital is suddenly scarce and expensive, is itself an opportunity for incoming investors with capital to provide for those in need.

An old model dies, and a new model rises. OK.

What makes somewhat less sense is the notion that both the new model and the old model are both gonna be just fine.

The prevailing sentiment seems to be some version of “we’re going to make a ton of money on this bloodbath, but also there will be no bloodbath (or don’t worry, the bloodbath will be over there.)”

Personally, I think the old model has more cracks than its letting on, and I’m somewhat concerned by the eagerness for investment managers to raise new funds to bailout their old funds—well not their funds, but funds exactly like theirs.

Reasonable minds can differ, of course, but they must agree that if someone is rescuing, then someone else is being rescued. It can’t be a smashing success for everyone.

And yet, there does not appear to be an agreement on that point.

Consider this a SitRep on the ongoing saga.

Valuations seems very optimistic

Jeffries put together a performance chart for the largest Private Equity firms and it’s a little surprising:

The biggest PE shops have been steadily marking up their books for the past year, since Q4 2022.

Here’s another look from the broader universe of PE funds:

In 2022, funds dutifully made some mark-downs (although not comparable to their pandemania era markups), but otherwise, it’s been up-and-to-the-right.

Does that make sense?2

Sure, 2023 has been a good year for the stock market, but public market returns have been driven almost entirely by the very largest companies, and PE tends to invest in the opposite of that.

PE tends to invest in smaller, often levered and/or unprofitable companies, of the sort that have been disfavored by the public markets. Heck, not even PE firms will touch those companies now (unless, of course, they already did, in which case everything is just fine).

That being the case, you’d expect to see PE returns going negative, or at least staying flat.

What do PE portfolio companies have that say, the Russell 2000 does not?

PE firms have ~6% better returns, that’s what (apparently).

Random Walk isn’t buying it.

Private capital managers are putting on a good face, mostly because they are extremely motivated to be optimistic, but it’s hard to believe they can keep it up for long.3

To the extent anyone is buying, they’re buying at a discount

In their defense, Private Equity will fairly say that it’s not fair to compare them to a highly liquid index.

Their assets are held privately. They are less liquid, and therefore there is less volatility. Things are down now, but they could be up tomorrow, and there’s no reason to get all worked up about the day-to-day changes in public markets.

That’s true.

But even if they’re relatively less liquid, they still do need liquidity at some point, and to the extent anyone is actually transacting in their book, the numbers aren’t great.

Exit activity by deal count has gone backwards by a decade:

Deal value is a third of what it was during the pandemania good times, so whatever these companies are worth, few people are offering prices that anyone is willing to accept.

Likewise, “stake pricing” (i.e. when one LP sells their stake in a PE fund to another) reflects at least a 9% discount:

Is that terrible? Nope, it’s actually not that bad at all, but it still seems inconsistent with an otherwise growing NAV.

Also, for a lot of Private Equity, the lines between PE and VC have been blurred, and VC is performing considerably worse.

Finally, the cost of new debt—secured by the same assets that have apparently appreciated—is considerably more expensive. LBOs are just one slice of the market, but both the equity contributions of the borrower and the yield-to-maturity are higher, the latter especially:

Lenders are getting paid, which is good for lenders, but bad for asset values.

Things will get worse before they get better

Another reason to doubt the rosy picture is that things are going to get worse, before they get better—again, that’s not controversial because that’s exactly what the big Private Capital/Credit funds that are currently the rage are banking on.

Companies that raised a bunch of money when money was cheap can (and are) play out the string for a bit, but eventually they will run out of money.

When it comes time to raise again (or exit), they will have to either (a) pay a lot more for the money (and therefore be worth less), or (b) fail to afford new money at all (and therefore be worth a lot lot less).

So what will it be?

Wall of maturities is coming

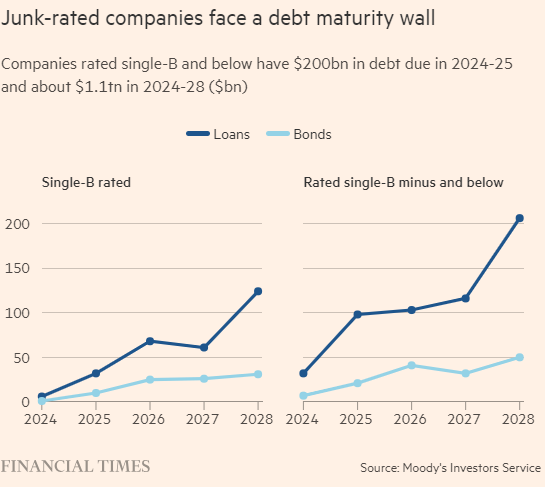

Sticking with the FT for a moment, defaults among portfolio companies are already rising, and there is a “wall of maturities” coming over the next couple of years which will require companies to refinance at increasingly higher rates:

In fairness, 2025 looks pretty manageable for B-rated companies, but for lower-rated companies there’s $200B that will need to be refinanced, and the number is only getting higher.4

Interest coverage is evaporating

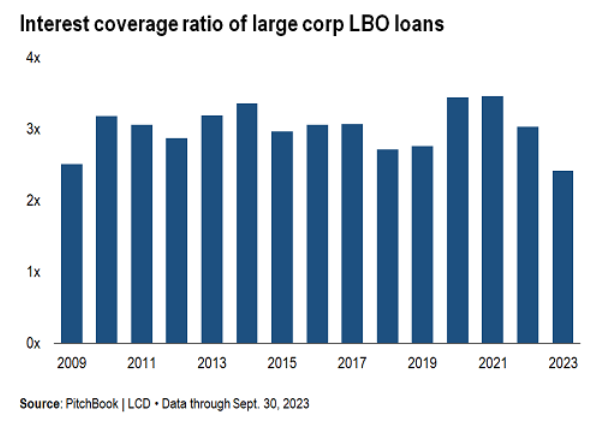

As it is, interest coverage ratios and Debt/EBIDTA—basically how much cushion a company has to pay for its debt—have already shrunk:

If you bought a company with debt with the expectation of using the company’s revenue to pay for that debt, then your cushion is now substantially smaller.

If you want to see something really alarming, take a look at this.