But how is the consumer really?

Thinks on start up failures, faux-lock-in, WFH, 1 hour commutes and the Almighty Consumer. Reads on Big Decisions, Verily, Reinventing Utopia, Community Notes, The Great Saddening

Random Walk was extra productive and heard from some people that Friday is a weird time to post. I’m not sure, but either way, lucky for you, it’s a Thursday Thinks and Reads:

The Thinks:

Startups are failing and that’s ok

Lock-in or Boomer-in or the real reason no one is selling their house

WFH v. Return to Work. What’s the data show?

The magic of 1 hour commutes

A check-in on the Almighty Consumer. Some good, some meh.

The Reads:

Big Decisions (even smart people make bad ones and sometimes they turn out good anyway)

Google’s insurance spinout Verily

Reinventing Utopia

On Community Notes from the founder of Ethereum

What Happened in 2012 or words with data-pictures on the Great Saddening

As per always, read, share, refer, and enjoy—really, if you like it and want to help me make more of it, please do click that big Refer a Friend button. Don’t be shy. I’ll be right here with you the whole time.

Random Walk is an idea company dedicated to the discovery of idea alpha. Find differentiated data, perspectives and people, and keep your information mix lively. A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds. Fight the Great Idea Stagnation. Join Random Walk.

Random Walk Thinks

Startups are failing and that’s OK

Everyone know s that start ups are closing more often now than they did before. There are also more down-rounds and “sold-for-parts” M&A. It goes hand-in-hand with the fact that money is tighter, and the “conveyor belt” of stage-investing is log-jammed at the final stage (IPOs).

RW and others have made the point that this is mostly a healthy correction from the fevered pitch of the past few years where anything and everything could get funded on the premise that those dollars could generate revenue-growth (but not profit-growth), which would inspire a subsequent round of funding (generating returns for the initial investment), and so on and so forth. That was a bag-holder model, a momentum-trade that worked until it didn’t, and basically dumb and bad. Good riddance.

As Hunter Walker recently put it, the current closures are basically three groups of companies (and I’m paraphrasing):

pre-pandemania companies that would have shutdown already if not for pandemenia;

pandemania companies that either should never have been funded or are failing in the normal course of expected high rates of traditional startup failure;

some mix of 1 and 2 that have enough money not to fail (for now), but have little prospect of ever raising money again with their current businesses, so their failure is being “pulled forward” because that’s the sound smart thing to do.

Walker’s taxonomy is useful enough to share on its own, but RW would add one wrinkle: some businesses are failing because the product they tried to sell was never a “low-touch, high-volume” sort of thing. It’s not a business fit for venture (as opposed to a venture-backable business that just didn’t make it, as most don’t).

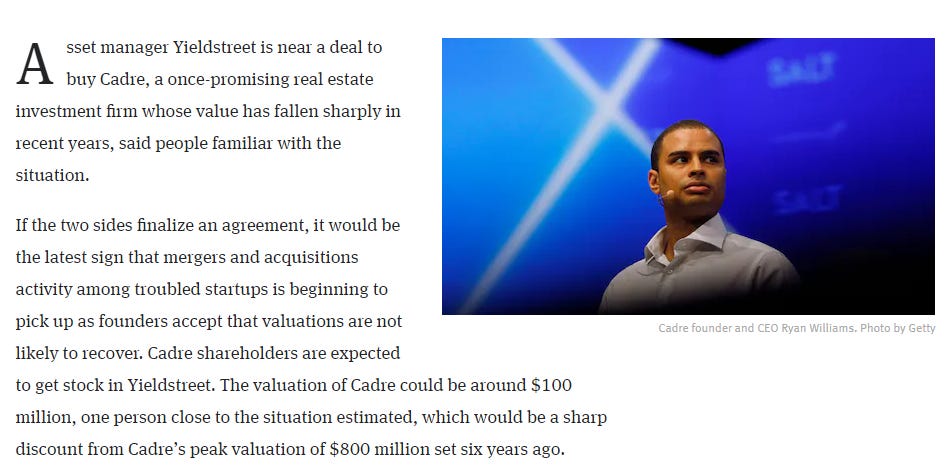

Personally, I’d put Cadre in that bucket. Cadre is a platform for real estate investing, giving users the opportunity to “invest alongside institutions.” It’s being sold (maybe) to another alternative investment platform, Yieldstreet, for what is likely something slightly more than parts.

But here’s the thing (which has always been the thing): the best real estate sponsors don’t need to put their deals on a marketplace, and therefore the best LPs in those deals do not need a marketplace to find them. The relationships and transaction costs of the high touch, low volume offline product are the moat. Why would any institution want to “invest alongside” an individual (however much an individual would like to “invest alongside an institution”), if they don’t have to? Whatever makes it to a marketplace like Cadre is most likely a lemon, especially when Real Estate investing suddenly gets hard again (now that rates have gone up).1

This is a long way of saying what I started out saying: nature is healing. The hype and status around the venture ecosystem made it seem like every business was a venture-backable business, and the only way to build a business was to go through venture-backing. I love the venture ecosystem, but it’s not true now and it wasn’t true then.

Lock-in or Boomer-in?

RW has long been disdainful of the “mortgage lock-in” theory of a sluggish real estate market. “Lock-in” is just a euphemism for unrealized-losses. People are “locked-in” in the sense of “I can no longer afford the house I would have bought, and no one can afford my house at the price I hoped to fetch, so unless everyone decides to offer a discount at once, we’re all just staying still.”

In furtherance of my claim (sort of), Apricitas Economics points out that, contra-lock-in, nearly 42% of homeowners have no mortgage at all, and another ~20% have very little mortgage left:

You can’t be locked-in by a mortgage you don’t have.

The truth is that the most likely inference one can draw here is that Boomers own a lot of homes and they really don’t sell very often—as per last week, we’ve been increasingly sedentary for a while.2 Mr. Apricitas quipped:

Eventually those boomers will sell, and the math says there are more sellers than buyers. Housing shortage indeed. We shall see.

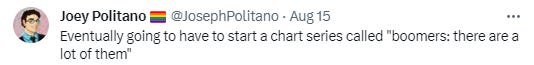

Meanwhile, the housing market in another aging, credit-tightening country is beginning to realize its losses:

The losses may be so serious, that some speculate China is fudging the numbers:

Analysts say the methodology, which partly relies on surveys rather than price data from transactions, helps authorities to smooth the trend and to avoid large swings. By contrast, in the US, the widely cited S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller indexes use home-price data collected at local deed recording offices across the country.

Private data paints a grimmer picture:

Idk.

It’s certainly true that recorded deed pricing (what Case-Schiller uses) is more reliable than surveys . . . but recorded prices don’t capture certain concessions, like mortgage buy-downs, etc., so they’re not perfect.

WFH v. RTO

Whether we’re WFH or Return to Office (“RTO”) is a bit of an open question. The datas tell slightly different stories, as do the anecdotes, but it seems like hybrid at least is still going the most strong. Post-Labor Day data will send a more meaningful signal.

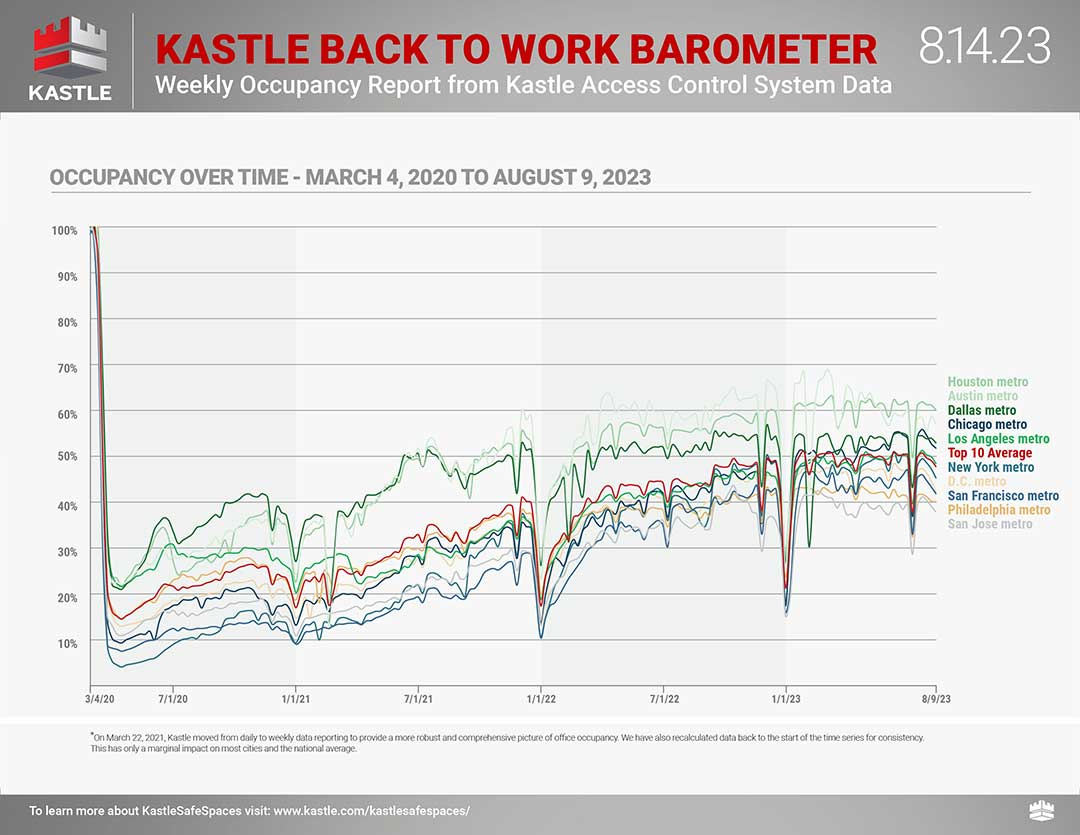

First, the card swipes say that the glass is still half-empty:

Other than Austin and Dallas, every other metro saw an in-office slide for the second week of August. Again, it’s the summer time, so it’s not telling you much.

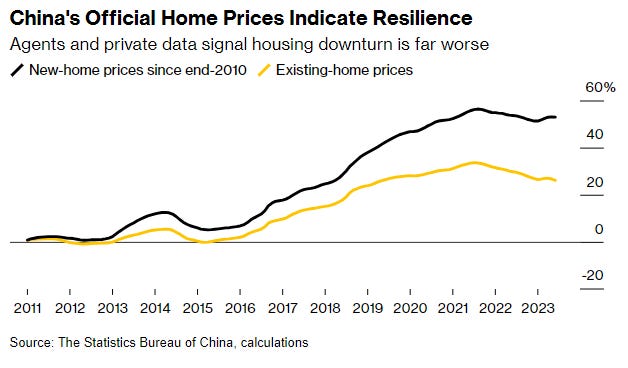

Cell data tells a somewhat different story, and it suggests RTO is gaining more ground (even if, again, the summer is a bit slow):

What’s interesting is that the trendlines—for both cell phone and card swipes—aren’t all that different, but they do show different plateaus and more variation between metros. They’re similar in that trendlines for all metros indicate that progress (or the lack thereof) has been somewhat muted for about a year. Just eyeballing the longer series, it looks like there was a small step-up post-Labor Day last year, but otherwise fairly steady:

The cell data above shows a similar plateauing around the same time. The big difference is that card swipes show lots of grouping around ~50% of occupancy, while cell phone pings range from 30% (SF) up to 70% (NYC).

I’m not entirely sure of what’s driving the difference between the two data sets, but one obvious possibility is that they’re not really measuring the same thing. The number of cell phones downtown includes tourists, as well as remote/hybrid workers who just aren’t coming into the office. Card swipes are just office workers, and really nothing else.

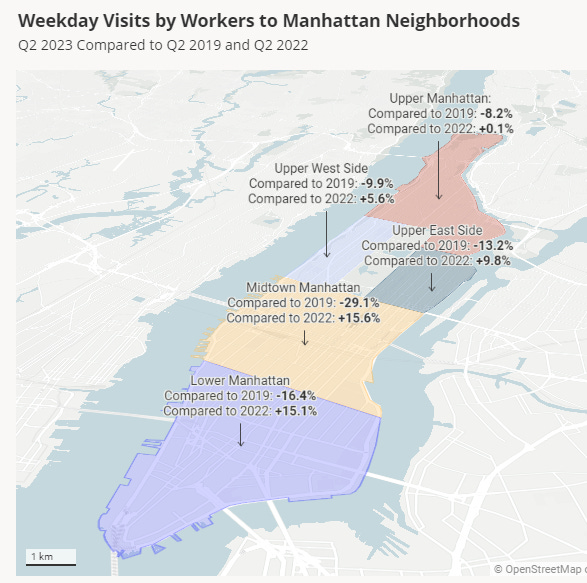

In NYC at least, a hybrid Tues-Wed-Thursday schedule seems to be the most popular, with those days capturing an increasingly large share of office visits (says the footfall data at least):

Note that these are shares, and not totals—2023 Wednesday doesn’t have more office visitors than 2019 Wednesday—it does have a higher share of the visits that are actually made. More simply, as people increasingly return, but only on middle-of-the-week days, then the Monday and Friday shares goes down.

Placer also makes the intuitive but still neat observation that commute-time matters to in-office participation. The longer the commute, the less in-office you’ll be (in Manhattan at least):

Midtown has the most longer-distance commuters (followed by Lower Manhattan) and it lags the overall recovery by quite a bit.3

Mass transit into NYC is pretty terrible. I can attest.

Best places to walk v. drive

Pretty pictures about commuting are really just a segue for me to introduce some other pretty pictures about commuting.

There’s an idea that One Hour is the commute time at which the tradeoff between cheaper-housing gives way to convenience. In other words, you can find cheaper shelter the farther you go from the city center, but at a certain point, you go too far such that the savings aren’t worth it. One hour is (supposedly) that “too far” point.

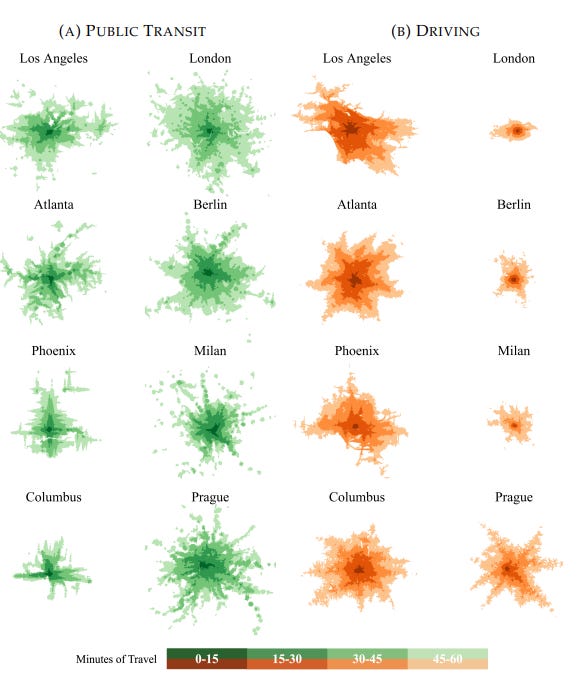

It stands to reason then that maximizing the amount of shelter within range of “one hour commuting,” and/or maximizing the range of the one hour commute, would be good things. Some intrepid researchers attempted visualize how well certain cities in both Europe and the United States did precisely that, and whether the commute range was accomplished by car, or by public transit.

The results are kind of neat:

European cities, other than Prague, are pretty terrible places to drive, but the public transit is pretty good.

Berlin and London especially have fairly substantial “accessible zones” (i.e. 1 hour commutes) by public transit, with substantially less accessible zones for cars.

The driving pattern in Atlanta is uncannily symmetrical. It looks like a starfish.

US cities unsurprisingly have a lot more driving access, but the public transit (in the sample at least) isn’t that bad. There’s definitely some room for improvement—Columbus especially, which just so happens to be the second fastest growing city in the country on a net migration basis—but Los Angeles was *much* better than I would have expected.

Anyway, if you hate cars, love density, and generally think people and insects have a lot in common, you will love this paper.

The consumer is mostly fine

A very good reason why we haven’t had a recession is that the ordinary American consumer is in pretty good shape. People are employed, their wages have gone up (finally in excess of prices), they’re spending, and from a borrowing/credit standpoint, they’re not in any danger zone. All of that is true despite substantial interest rate increases implemented explicitly to bring the pain.

RW has previously hypothesized as to why there hasn’t been much pain yet: (1) RW is just wrong about the underlying structural strength of the economy and its dependence on cheap money; (2) it takes time for the pain to materialize, and consumers are relatively insulated from the first order effects of more expensive money; (3) a substantial chunk of the pain has been moved to the U.S. Treasury where it sits like a an elephant-sized-time-bomb-in-the-room that won’t explode, if we all pretend it’s not there.

Anyway, the “health of the consumer” is a thing I check every now and again, both to see whether I’m becoming more right, and to see whether I continue to be wrong. These are mutually reinforcing endeavors. If I look for evidence that I’m wrong, then I’ve got slightly more confidence in the evidence I find that I’m right.4

Anyways, there’s some interesting stuff, so let’s dig in.