5 Idea Friday: EU lags; AI payback (to whom); It's getting better (reprise); The predictors; Nothing Ever Happens Index

A feast for thought, heading into the weekend

AI Capex is Big (but not everywhere)

AI payback (but to whom)?

You’ve got to admit it’s getting better (reprise)

The predictors, who are they?

Nothing Ever Happens Index

👉👉👉Reminder to sign up for the Weekly Recap only, if daily emails is too much. Find me on twitter, for more fun. 👋👋👋Random Walk has been piloting some other initiatives and now would like to hear from broader universe of you:

(1) 🛎️ Schedule a time to chat with me. I want to know what would be valuable to you.

(2) 💡 Find out more about Random Walk Idea Dinners. High-Signal Serendipity.5 Idea Friday

Five quick hitters on this and that for the weekend.

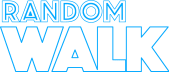

1. AI Capex is Big (but not everywhere)

If you want a good lesson on how not to get ahead, here’s one:

European “AI-related imports” are in decline from the ChatGPT starting point.

Europe appears generally uninterested in AI, except of course for the regulation part. That, they’re all over.

One can (justifiably) hand-wring about all the money that’s flying to AI, right now, but under-investing surely seems worse than under-investing. I’m not entirely convinced by the view that “once you get ahead, there’s no looking back” (especially considering how frequently the leaderboard begins to change), but it’s hard to figure “getting ahead,” if you don’t even try.

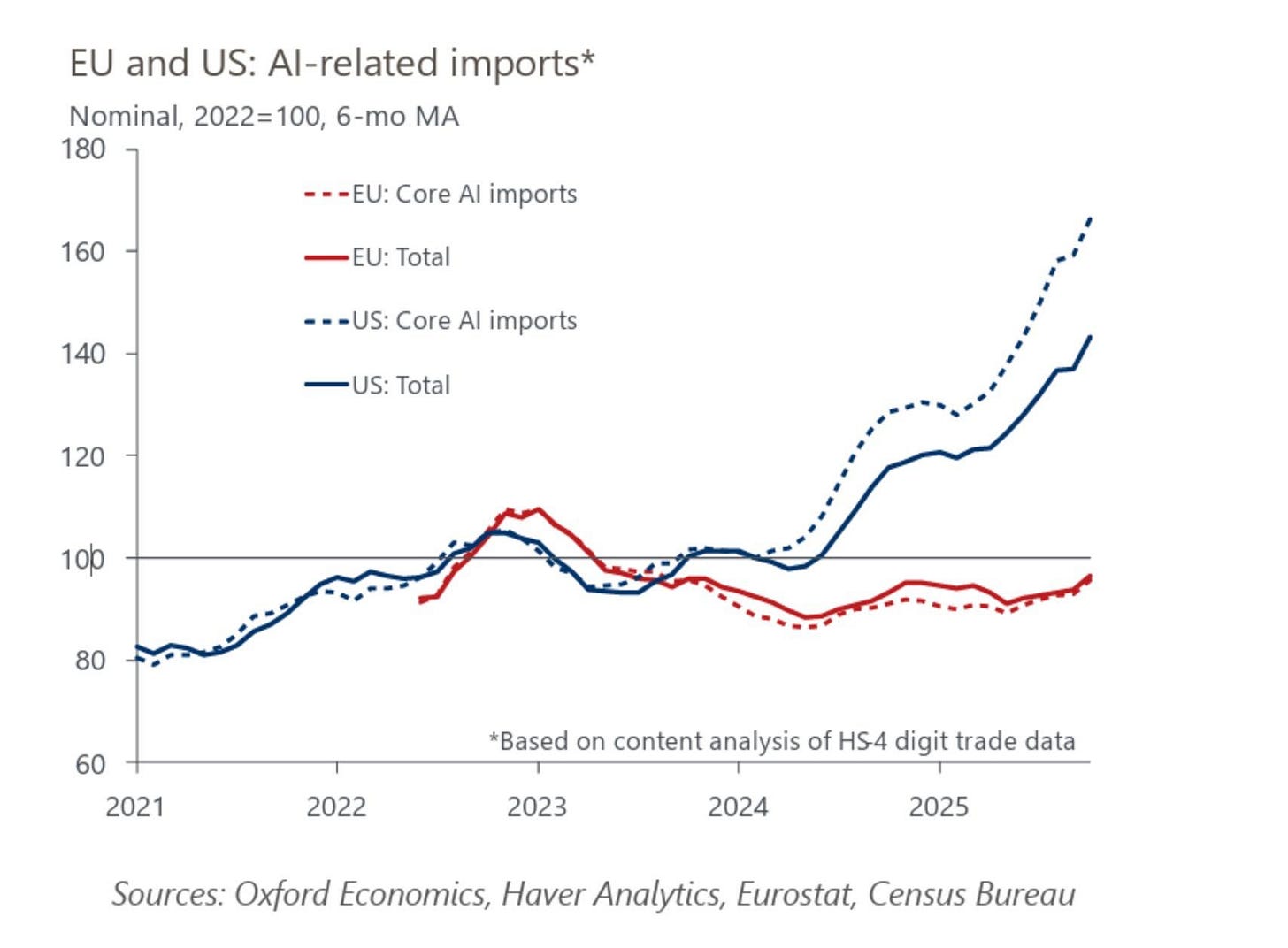

Anyways, while on the subject of AI investment, here’s yet another visualization of the scale of this thing:

Data centers are now ~2/3rds of infrastructure related deal volumes.

Back in 2020, data centers were just an itty-bitty stack. Fiber optic investment has gotten pretty large too.

And another one:

Cumulative change for Data Center construction spending is up ~338% since 2020.

Again, this isn’t new information, but I consistently find these visuals to be pretty striking.

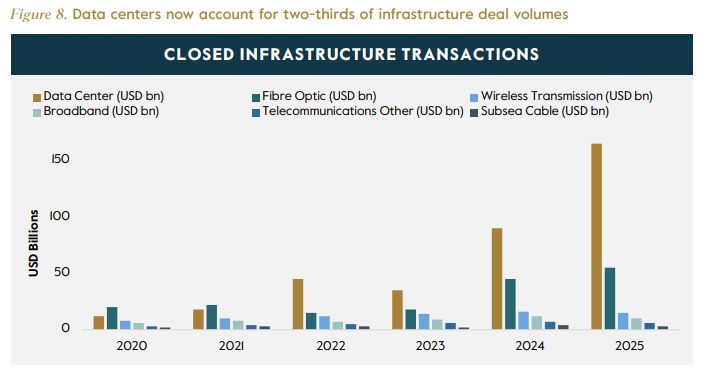

2. AI payback but to whom?

On the subject of AI investment, and especially payback on AI investment, this too is a point worth making.

Even if one is very bullish on the long-term gains of AI, it’s not obvious where those future rents will accrue (and to what extent).

For example, while the performance gains from frontier models continue to impress, the absence of any one clear leader, means that no one enjoys a relative advantage for very long. And as each iteration gets more expensive, the ability to recoup the upfront cost of model development, gets more and more challenging.

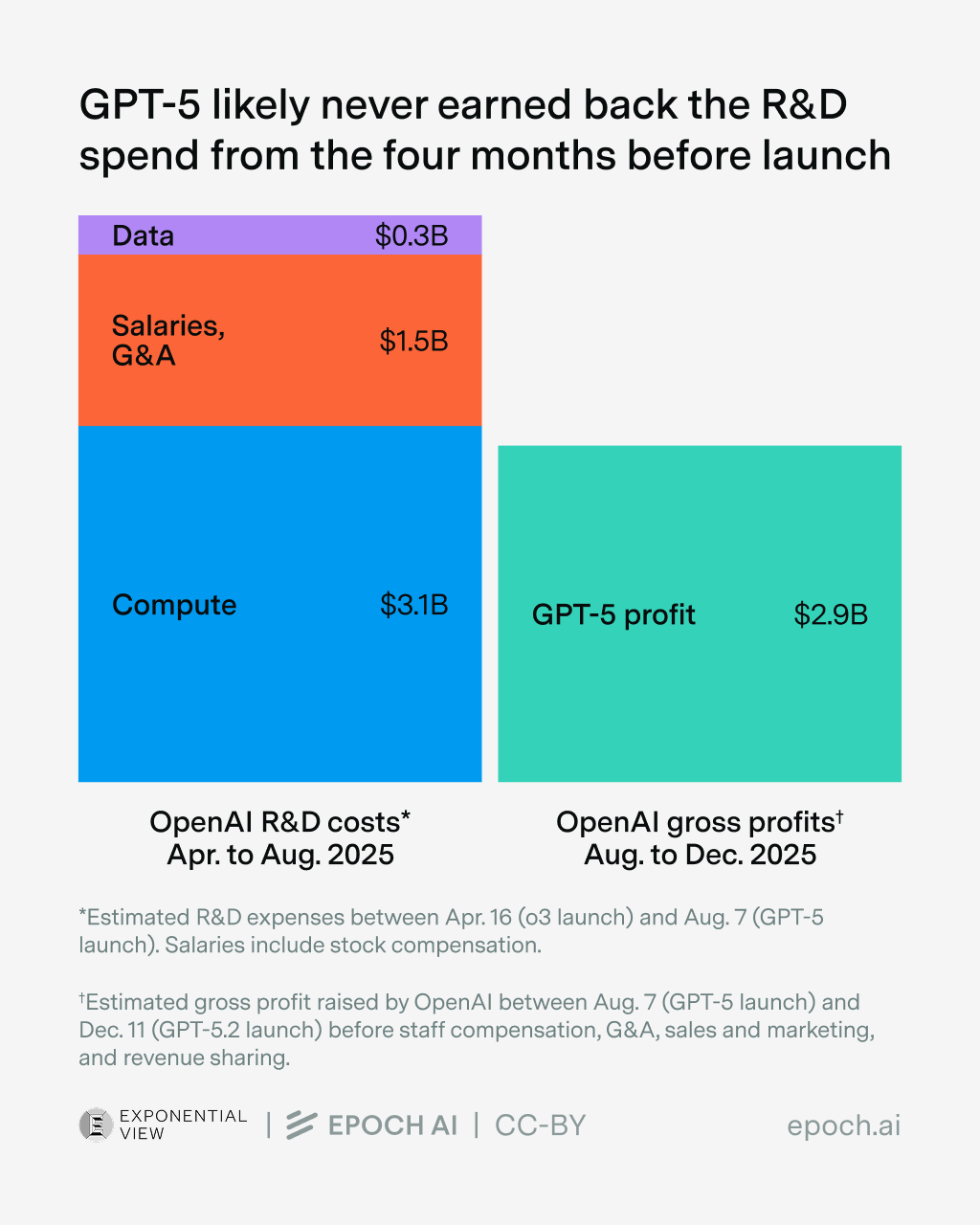

Consider some napkin math on GPT-5:

By this estimate, running GPT-5 created a ~$2B net-loss for OpenAI.

Gross margins for GPT-5 were pretty solid (~60%), but the sheer cost of running the OpenAI organization (and sharing revenue with partners) overwhelmed any of the profit.

And that $2B loss doesn’t even account for the R&D investment:

GPT-5 cost ~$5B to make, but generated only $2.9B in gross profit.

So, OpenAI spent ~3-4 months between the launch of o3 and the release of GPT5, and then after running GPT5 for ~4 months, it released 5.2. It spent ~$5B to make a thing that it rendered obsolete in a quarter.

5.2, for its part, was quickly surpassed by Gemini’s latest, as the newest hot model, and more recently, Claude Opus 4.5 lapped Gemini as the greatest thing since sliced bread. And that doesn’t even account for open source models, that lag the frontier models only by a few months. Likewise, at the application layer, many appmakers focus on model-routing, so that they’re optimizing for the best model for any given job, which makes stickiness even a harder problem to solve.

So, you see the problem here?

If a winner were to emerge, the prize would be enormous. But no one seems to have the secret sauce for getting and staying ahead, and the cost of being in the race is astronomical. It’s little mystery why these companies keep raising so much money, because capital is quite obviously a competitive advantage (in the sense of being able to compete, at all).

And yet, one does begin to wonder what precisely the end-game looks like, because this cannot go on forever.

Now to be fair, older models (and older GPUs) aren’t completely obsolete. And it’s not unreasonable to expect some domain competencies to emerge over time . . . but, otoh, these are “general purpose technologies,” so y’know . . .

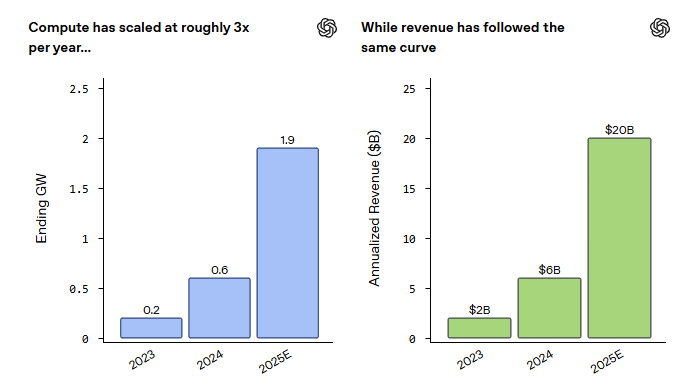

For it’s part, OpenAI claims that “revenue scales with compute,” i.e. the more compute they have, the more money they can make:

Looking back on the past three years, our ability to serve customers—as measured by revenue—directly tracks available compute: Compute grew 3X year over year or 9.5X from 2023 to 2025: 0.2 GW in 2023, 0.6 GW in 2024, and ~1.9 GW in 2025.

While revenue followed the same curve growing 3X year over year, or 10X from 2023 to 2025: $2B ARR in 2023, $6B in 2024, and $20B+ in 2025. This is never-before-seen growth at such scale. And we firmly believe that more compute in these periods would have led to faster customer adoption and monetization.

3x revenue growth and 3x compute growth, and so those are the same and forever linked, because that is how correlation works.

OK, alright.1

Now, maybe there’s just enough demand to go around that it doesn’t matter, and while it’s true that the big frontier boys keep one-upping each other, the big-boys club is still pretty small, so perhaps there is enough to go around. But for now, that’s obviously not the case.

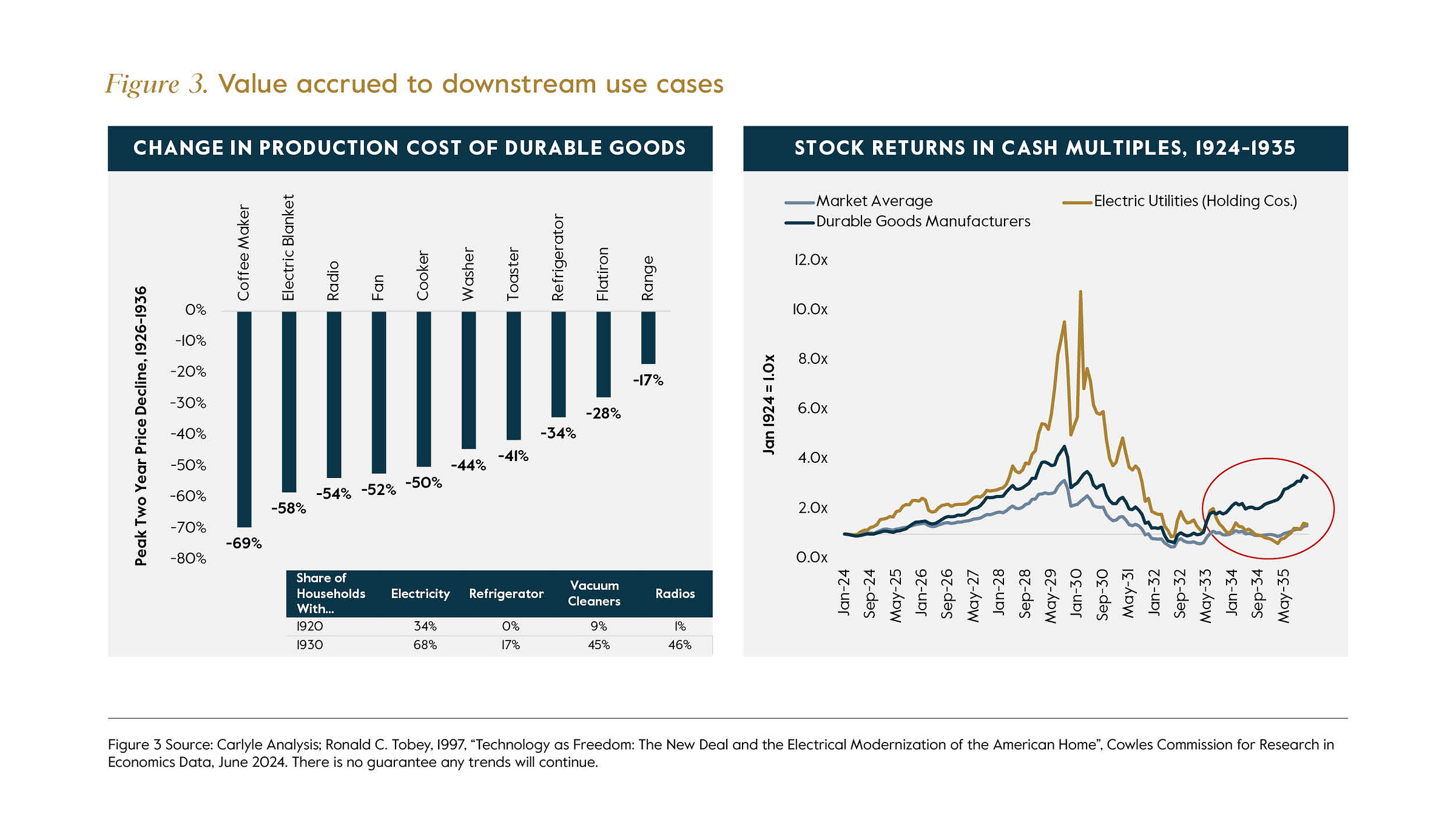

Another interesting analogy is to the last big grid overhaul at the turn of the 19thC into the 20th.

There too it was pretty obvious that electricity was going to be an enormous leap forward (and it was, and then some), but they don’t call it a commodity for nothing.

Ultimately, it wasn’t the utilities that captured the lions’ share of the gains:

From 1932 to 1935, stock returns for durable goods manufacturers quadrupled, while the utilities stayed pretty flat.

In other words, plentiful electricity was a boon for electric goods-makers, and less-so for the electricity-makers.

The analogy here is pretty straightforward: the benefits of LLMs could well be enormous, but the LLMs themselves, may have a hard time capturing that value directly. Heck, even the downstream users may have a hard time capturing value, inasmuch as being an “AI company” becomes table-stakes.

In that scenario, it’s the diffuse public that accrues the lion’s share of the value, which is great for the public, but some part of those benefits need to be roundtripped in order to keep financing this stuff.

ICYMI

3. You got to admit it’s getting better (reprise)

On the subject of the public winning again, here too is a brief reprise of “You’ve got to admit it’s getting better.”

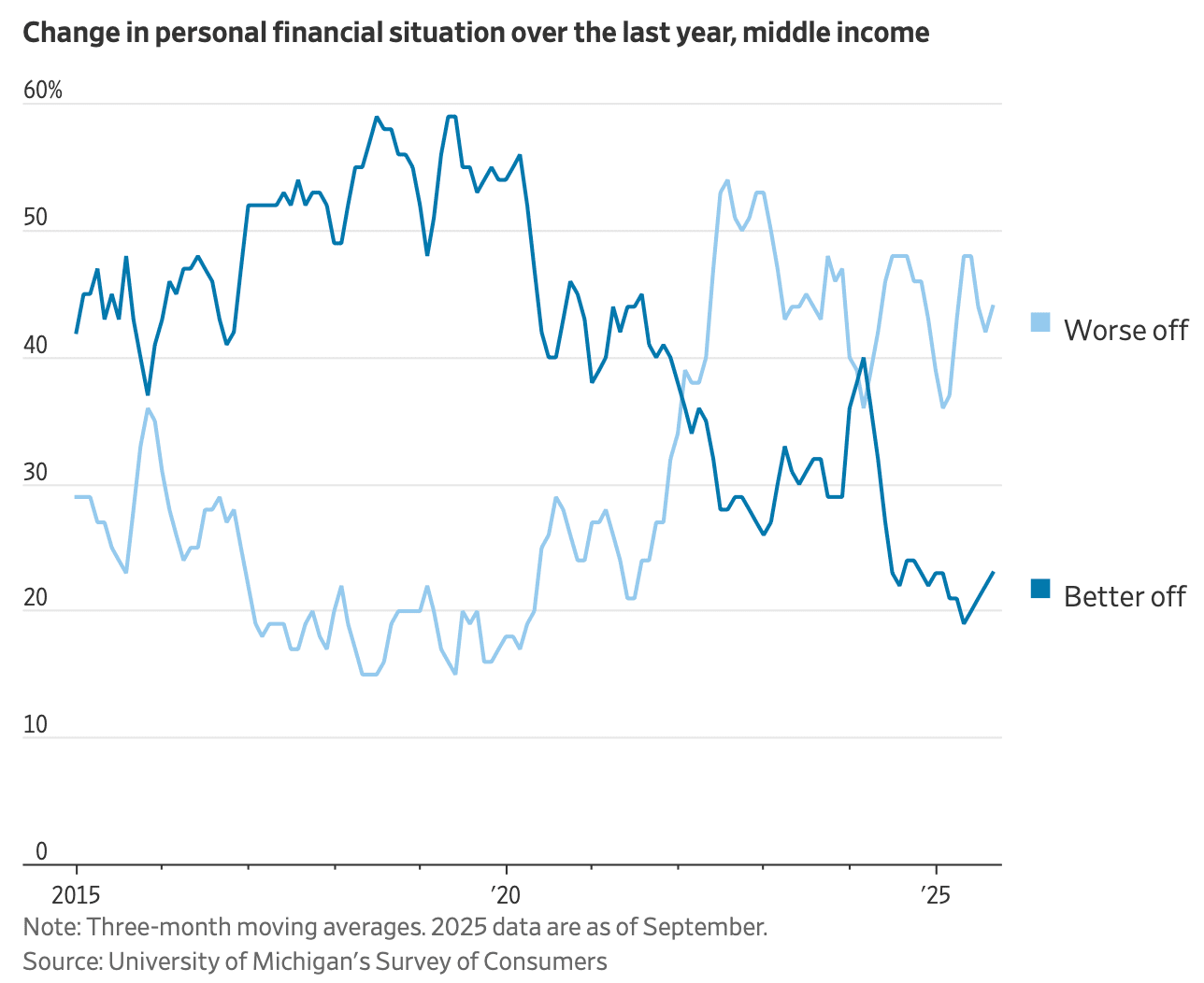

Once again, people are grumpy:

“Middle income” households have reported their financial situation as “worse-off” since ~’22.

So, yes, people feel worse off when the money spigot turned off. It doesn’t really matter that everything was getting more expensive around them, the velocity at which they were getting paid more (and leveling up the corporate ladder) was more than enough to make them feel good.

Well, to be fair, the decline really started with Covid, but then it accelerated again when rates went up.

The point here is that surveys about “consumer confidence” (which bears no relationship to consumer spending) aren’t telling you much about how people are in some absolute sense, but are telling you something about how people feel. And how people feel is a function of relative status, and the sense in which status upgrades are achievable (or not).

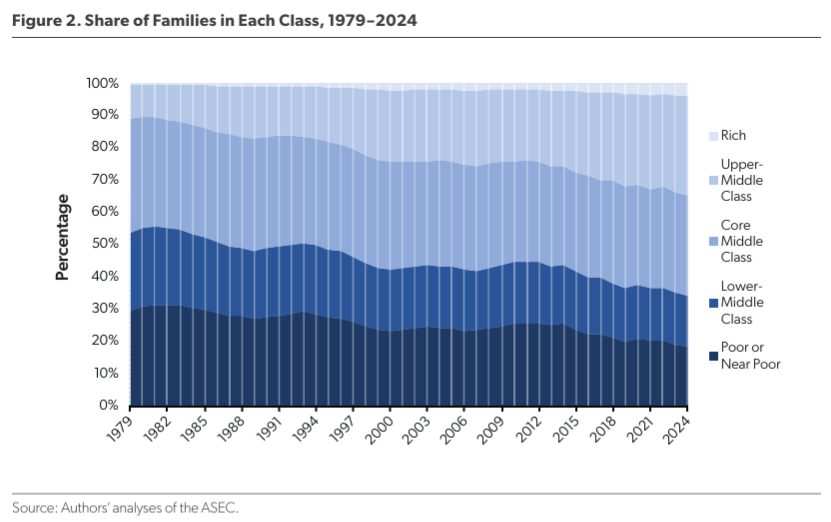

I mean, it’s true that the middle class is disappearing. That’s because the poor are disappearing, and the middle class is becoming the “upper middle class.”

The “upper middle class” has roughly tripled its share of families since 1979, while middle, lower, and poor classes keep shrinking.

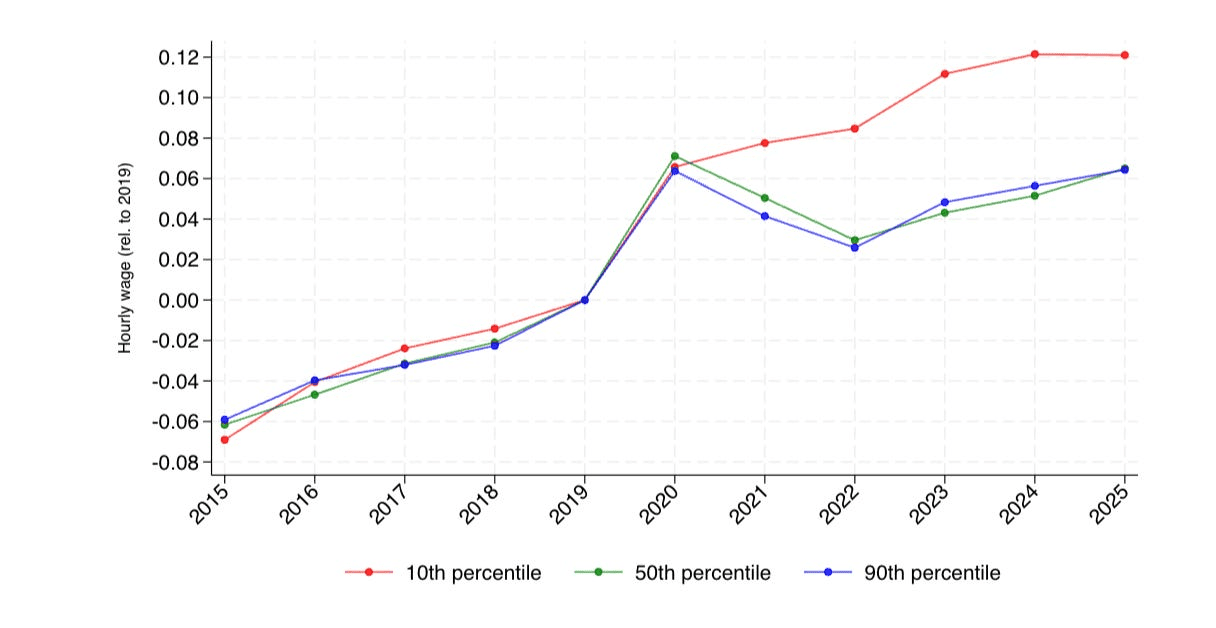

Likewise, remember that wage bump for lower-income service workers that took-off during the peak pandemic “labor shortage” (that Random Walk observed quite so obsessively)?

It’s still there:

Bottom decile wage growth is still substantially ahead of the mid-point and the top-decile.

And given the premium on lower-income service workers, it’s seems reasonable to expect that lower-income service wages will continue to grow a bit more quickly than the field.

Again, that doesn’t mean that everything is perfect, or that feelings should be ignored. It does mean, however, that confidence and feelings aren’t telling you much about material wellbeing. Or rather, material wellbeing is influenced by relative changes much more so than absolute ones.

And it’s a mistake to confuse the two.

4. It’s trading predictions, not betting

Prediction markets continue to rise in salience, and Random Walk has no particularly strong views, one way or another.

People like to place bets. It’s entertaining, and sometimes it’s valuable, insofar as it creates incentives to discover (and disseminate) information and insights about the world.

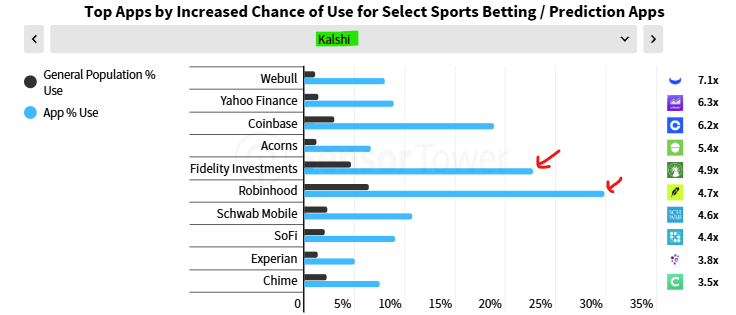

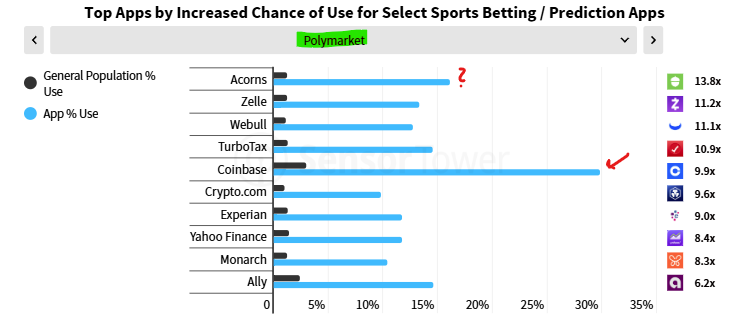

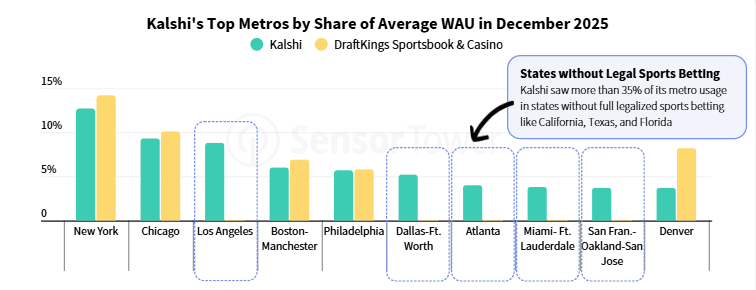

I did, however, find this little mini-profile of predictors somewhat amusing, specifically as between two of the leading platforms, Kalshi and Polymarket.

From an app-usage standpoint, Kalshi and Polymarket users are not the same:

Kalshi users have a lot of crossover with Fidelity and Robinhood (~5X the general population), two leading e-brokers.

Polymarket users have a lot of crossover with Coinbase (10x) and (weirdly) Acorns (14x), the relatively small roboadviser that you just don’t hear much about these days.

What’s to make of this? Idk, probably nothing, but it struck me nonetheless.

I suppose on possible implication is that Kalshi has taken the path of officialdom, having obtained CFTC oversight for its operations (while Polymarket only began that process very recently). That polymarket required a vpn may explain why there’s less crossover with very serious businesses like Fidelity (and Robinhood), compared to Kalshi.

Of course, Kalshi is doing some regulatory arbitrage, as well.

Kalshi has grown its book massively on sports betting predicting, and you’d never guess some of its best metro markets:

Kalshi generates ~35% of its metro userbase from markets where sports betting is not (yet) legal.

To be fair, Kalshi has pretty good penetration in markets where sports betting is legal, too, so clearly it’s not all regulatory arbitrage. But, it’s definitely some.

5. Nothing ever happens index

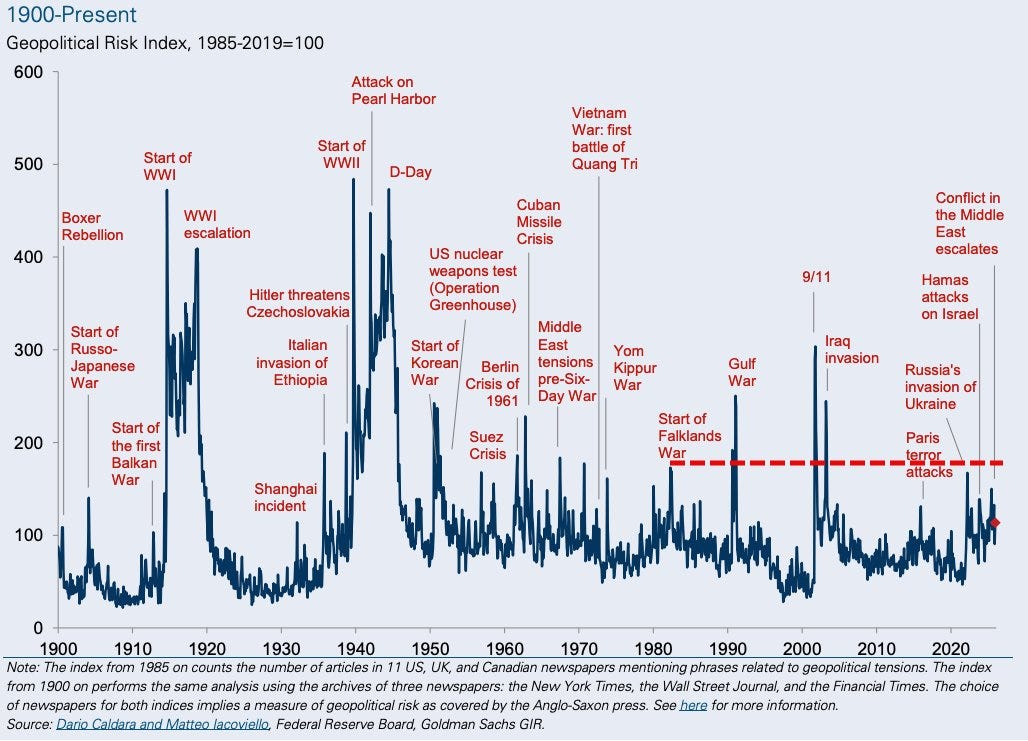

And finally, with all the breathless situation monitoring around Iran, this one is just kind of fun.

Here is how “geopolitical risk” events have historically been attended to by the leading papers of record (as measured by Goldman Sachs):

Spikes around all the various armed-conflicts, which is pretty much what you’d expect.

It’s pretty striking, though, that the Falklands War got more attention than pretty much any global conflict in the last 45 years (outside of the Gulf War, 9/11 and the subsequent invasion of Iraq).

I mean, who remembers the Falklands War? Maybe we should? It’s before my time, but was it just an otherwise slow news cycle? Did people overstate the significance? Or have we forgotten about it for other, perhaps less-good reasons?

Idk.

Previously, on Random Walk

Private Credit and Insurance, two peas in a pod (reprise), and a chart dump on default rates

five charts on the rise of private credit in life insurance

Energy in 1776

It’s July 4th, so Happy Birthday America, and we’re going to keep it light and only semi-topical.

Random Walk is an idea company dedicated to the discovery of idea alpha. Find differentiated data, perspectives and people, and keep your information mix lively. A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds. Fight the Great Idea Stagnation. Join Random Walk. Follow me on twitter. Follow me on substack:

That isn’t to say that compute isn’t a throttle on monetization. I think that it is, and that the foundation models have generally taken an approach of releasing the good stuff, and then when compute blows up, they take it away unless you charge more. Seems smart. But…two lines went up 3x doesn’t not a causal relationship make.