5 Idea Friday: market viz; zombie funds; still no housing shortage; illiquid becomes liquid; bring your own energy (coal too)

A feast for thought, heading into the weekend

a pretty viz of market diffusion

PE chart dive, of zombie funds, revisited

definitely no housing shortage (and supply-constraints explain basically nothing)

productivity gains do the darndest things (to previously illiquid credit markets)

bringing your own energy (and the grid backlog)

burning coal to keep the environment clean

👉👉👉Reminder to sign up for the Weekly Recap only, if daily emails is too much. Find me on twitter, for more fun. 👋👋👋Random Walk has been piloting some other initiatives and now would like to hear from broader universe of you:

(1) 🛎️ Schedule a time to chat with me. I want to know what would be valuable to you.

(2) 💡 Find out more about Random Walk Idea Dinners. High-Signal Serendipity.5 Idea Friday

Five quick hitters on this and that for the weekend.

1. Market diffusion visualized

For all the data-viz enjoyers, this was just a neat look at the Friday morning price action (courtesy of @chartfleau):

Semis up, hyperscalers down, and all those little industrials, still bubbling to the top.

It doesn’t mean much (other than diffusion is back for the index, and so long Mag-?? being the only game in town).

Mostly, I just thought it was pretty.

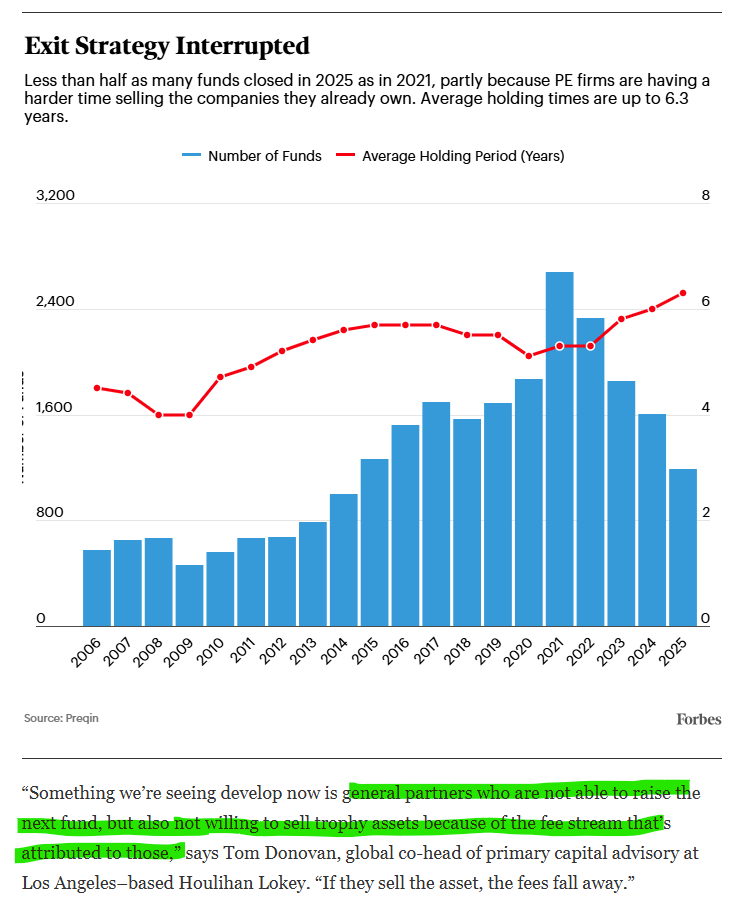

2. “Zombie Funds” and No Exits for Private Capital (reprise)

Somewhat as a follow-on to the chart-dive on PE, lots of readers sent me this Forbes piece on “Zombie Funds.” It’s got some more anecdotes related to the point, and it even has a list of 20 midsize zombies, struggling to raise their next fund.

For my purposes, I suppose this was really the only color worth adding:

You can’t raise, if you don’t sell . . . but if you sell, you don’t have AUM to generate fees.

And yes, selling to get liquidity does increasingly require biting the bullet on price:

The average “uplift” on valuation at exit has been declining since ‘22, and has now gone negative.

It was only a matter of time, but this is the ‘mistakes were made’ backlog clearing. It’s an inevitable and healthy correction because there never was going to be a ‘back to normal.’

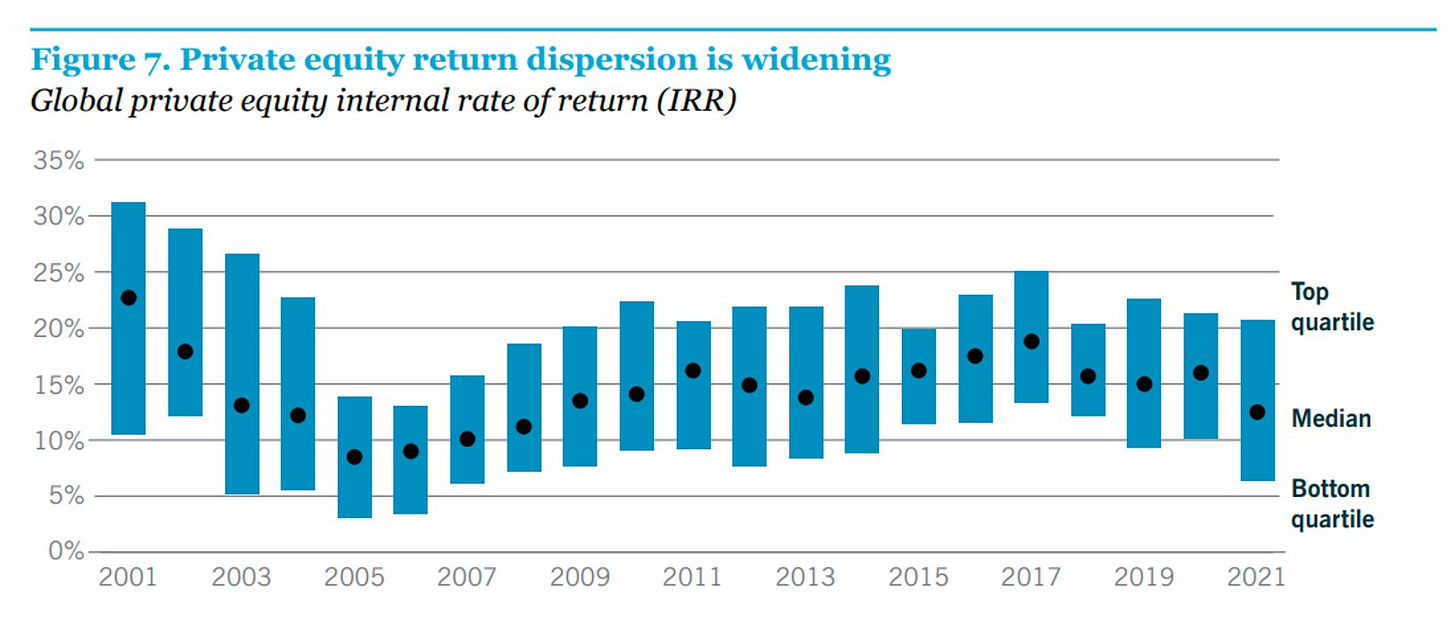

Wouldn’t you know it, but return dispersion for PE is widening:

The gap between the best and worst is as wide as its been since the DotCom days.

Some funds are taking their medicine. Others are still waiting to do so. Life will go on.

In the bigger scheme of things, the principal-agent misalignment, in this case, a bias towards the bird-in-hand (i.e. fees), explains far more of capital markets, than people think.

ICYMI

3. SF Fed: There is no housing shortage. Prices are explained by incomes

In the latest annals of ‘of course there is no housing shortage, and zoning has little to do with anything’ the SF Fed has entered the chat:

A large body of research has argued that housing supply constraints can explain this divergence . . . However, recent research has shown that supply constraints cannot account for differences in house price or supply growth across U.S. cities (Louie et al. 2025a, b).

. . . regulatory reforms may have limited impact on housing affordability and that differences in housing supply constraints are not the fundamental drivers of differences in housing dynamics across metro areas.

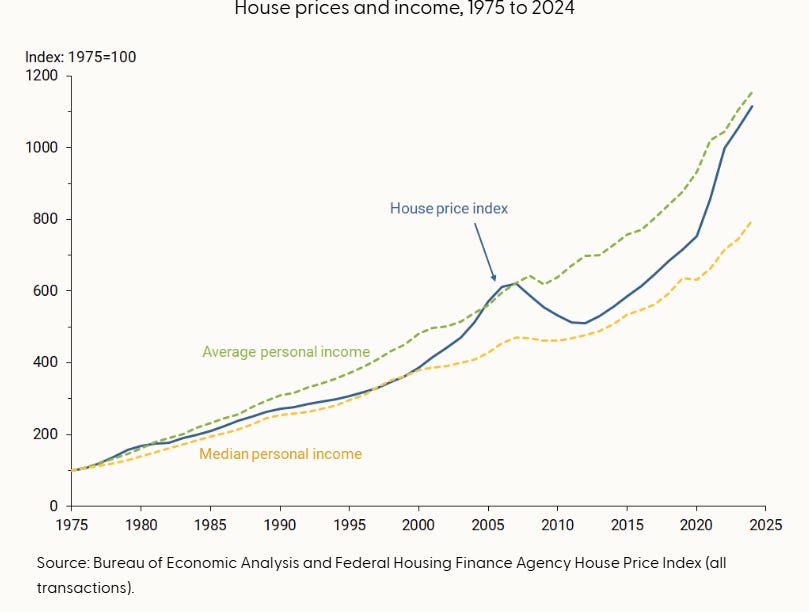

. . . Average income, an indicator of housing demand (green dashed line), grew essentially one-for-one with house prices from 1975 to 2024, even though median income failed to keep up.

In other words, house price growth may simply reflect growth in housing demand, driven in part by growth in average income, such that questions of housing affordability may primarily be about differences in income growth at the top of the distribution relative to the middle.

It’s almost like home prices rise when people have the ability to pay more for housing, especially where there is a big divergence at the tails, i.e. when the average income skews higher than the median.

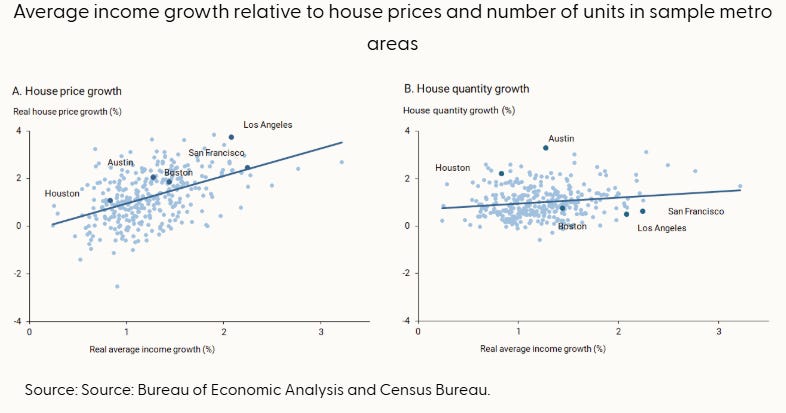

And zoning, or really, net-new supply of shelter, does not appear to explain inter-metro price differences, at all:

Panel A . . . shows that growth in average income is strongly positively related to growth in house prices: On average, income growth across metro areas moves one-for-one with house price growth

panel B shows little connection between average income and annualized growth in housing supply . . . [s]ome metro areas experience high income growth but little growth in housing supply while others experience relatively little growth in income and large growth in quantities . . . as income grows, there may be little effect on the demand for housing supply. If we control for population growth, there is essentially no relationship between the two.

Home prices scale with incomes, but home quantities, do not.

In other words, if you get a lot of new people, who aren’t all that wealthy, supply increases, but not so much prices (e.g. Houston). If, on the other hand, population remains relatively stable, but incomes rise (on average, so driven by the tails, e.g. SF), then prices go up, while supply stays even.

It’s almost like that when there are new bodies needing shelter, then new shelter arrives. The prices of that shelter, though, are driven by the incomes of the bidders. Wealthy bidders make prices go up, while less-wealthy bidders, do not.

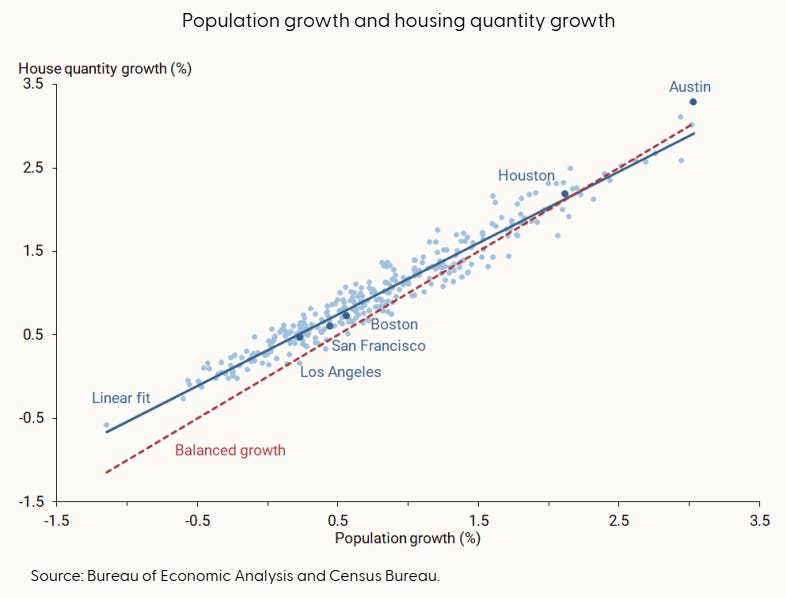

Not only is supply relatively responsive to demand, there’s actually some evidence of “over-supply,”:

[A]bout 85% of metro areas had more growth in housing quantities than in population; this is shown by most of the data lying above the dashed red “balanced growth” line, which indicates the housing growth rate that would match population growth with no change in average household size.

There’s been even more housing that population growth would predict!

Put it all together, and you can think of demand for housing as some product of the number of buyers x their incomes.

Lots of new people with high incomes? Supply and prices rise.

Lots of new people without high incomes? Supply rises, but prices do not.

The same number of people, getting wealthier? Supply is flat, but prices rise.

As the SF Fed concludes:

differences in the composition of income growth and its translation into housing demand—as opposed to differences in housing supply—can explain both the higher average price growth and low growth in quantity in some metro areas relative to others

Sorry, shortage bros, but there is quite obviously no housing shortage.

It doesn’t seem to matter how much evidence piles up to the contrary, the narrative is just too appealing to wonks, centralizers, and the industry (not to mention the status grievances of the benighted everyone) that it remains a truism, even when it operates as a contradiction in terms:

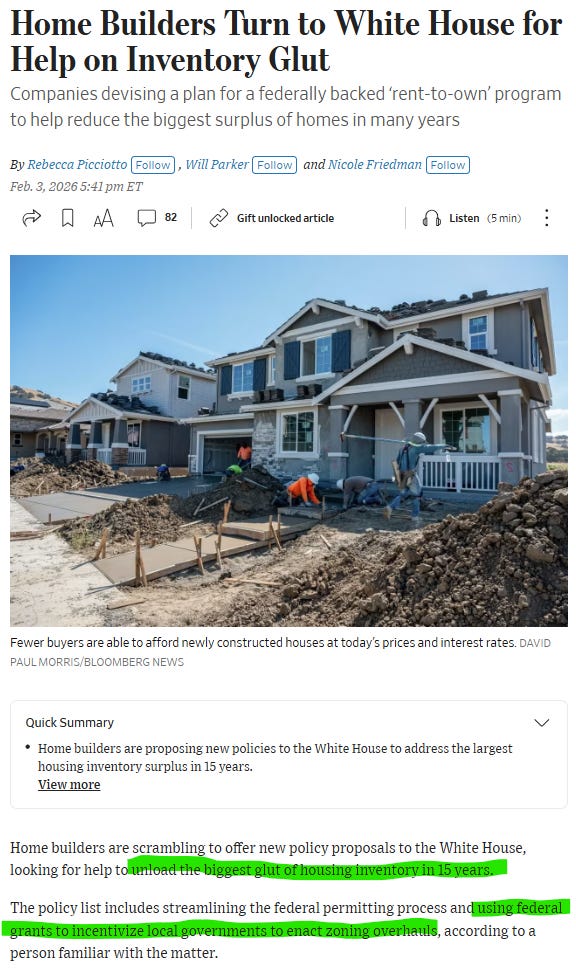

We need radical housing interventions to solve . . . “the biggest glut of housing inventory in 15 years . . . using federal grants to incentivize . . . zoning reform.”

Shortages, gluts . . . doesn’t matter. All signs point to “zoning reform.”

OK, alright.

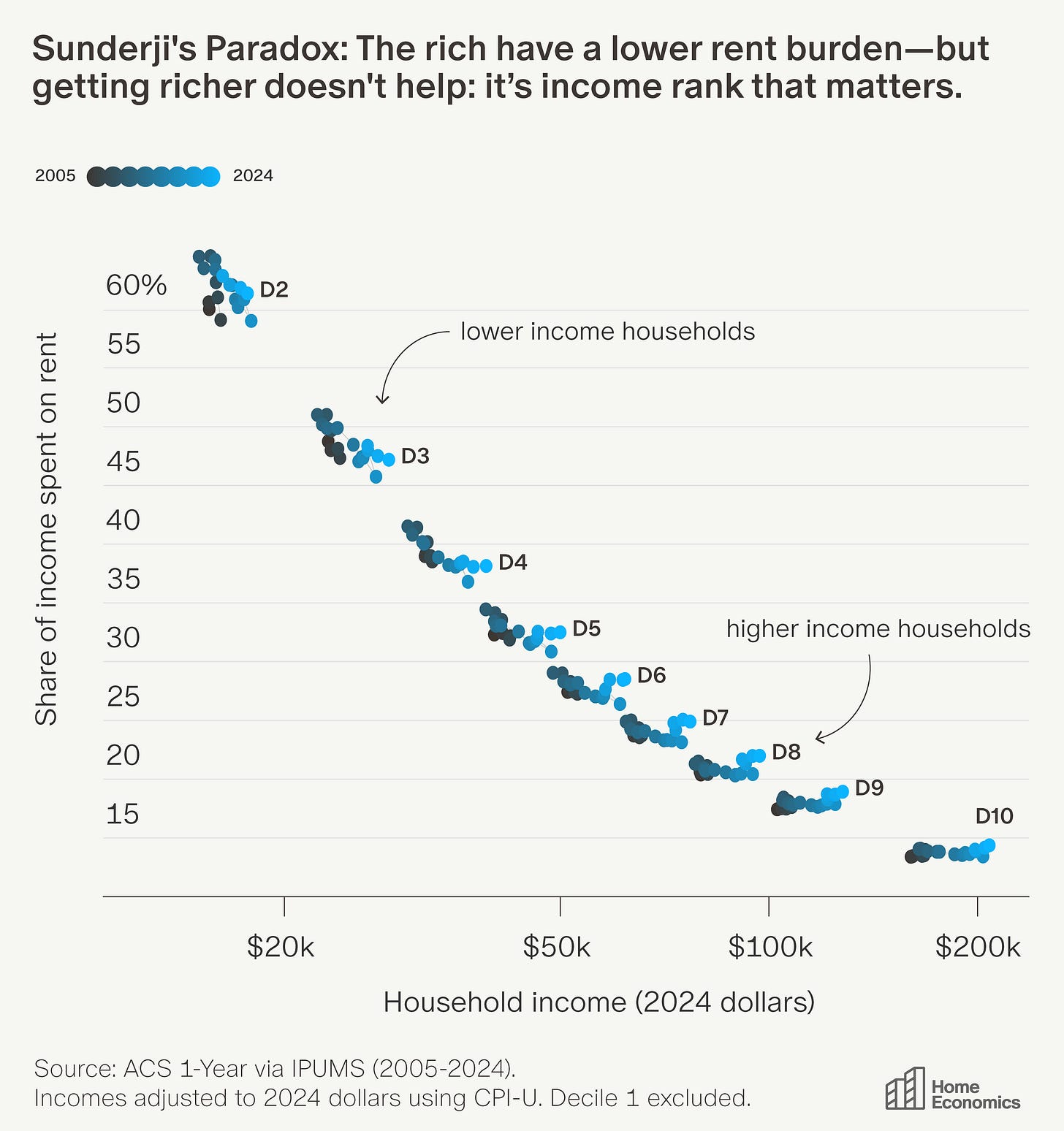

As my friend Aziz Sunderji recently pointed out (again):

the entire concept of “housing burden” is incoherent. The department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines households spending more than 30% of income on housing as “burdened.”

But if the median household has spent roughly 25–30% across all these settings—in Berlin in 1868, in rich countries and poor countries, in regulated markets and unregulated markets, in every U.S. Consumer Expenditure Survey since the 1930s—then 30% isn’t a burden

The median household pays ~25-30% of income for shelter, and that’s been true for about 100 years, wherever you look—in the US, Berlin, wherever.

If that’s “burdened,” then everyone is burdened.

4. Making the illiquid, liquid

This one is a bit obscure, but I thought it was kind of fun.

It’s more an illustration of the downstream effects of technology-driven productivity gains that can be quite massive, relative to how much attention they get.

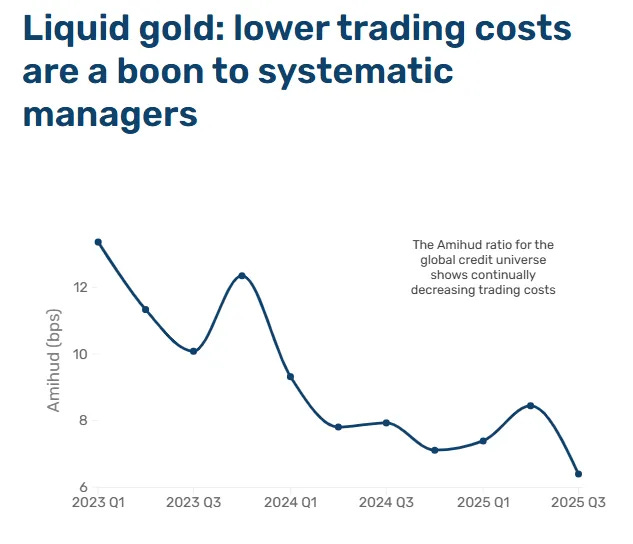

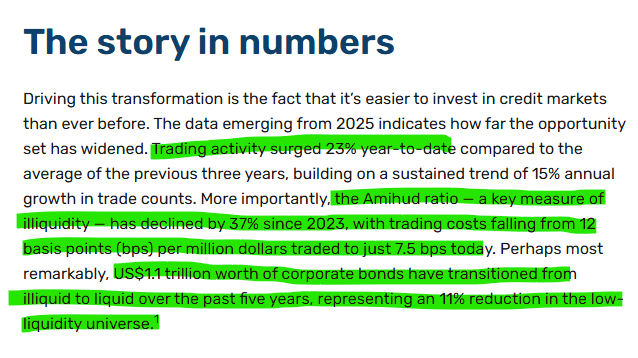

In this case, the backend technology for credit markets has been getting better and better. The net result is lower transaction costs, a lot more trading, and a lot more liquidity, particularly to previously illiquid parts of the credit markets:

Better tech, means lower transaction costs, means more trading and more liquidity.

A ~40% decrease in trading costs has unlocked ~$1.1 trillion in previously illiquid corporate bonds, “representing an 11% reduction in the low-liquidity universe.”

I’m not exactly sure how that translates into GDP, but it seems like a good thing (and a big deal) that 11% of the illiquid bond universe became liquid in just the past 5 years.

Productivity gains manifest in all sorts of ways that we don’t really anticipate or appreciate. That is all.

5. Bring your own energy

I recently listened to an episode of Odd Lots whereby a very smart-sounding person made the argument that there is no energy shortage, and in fact, everyone is overbuilding energy capacity to meet the substantial rise in demand.

Maybe so. It’s worth listening to.

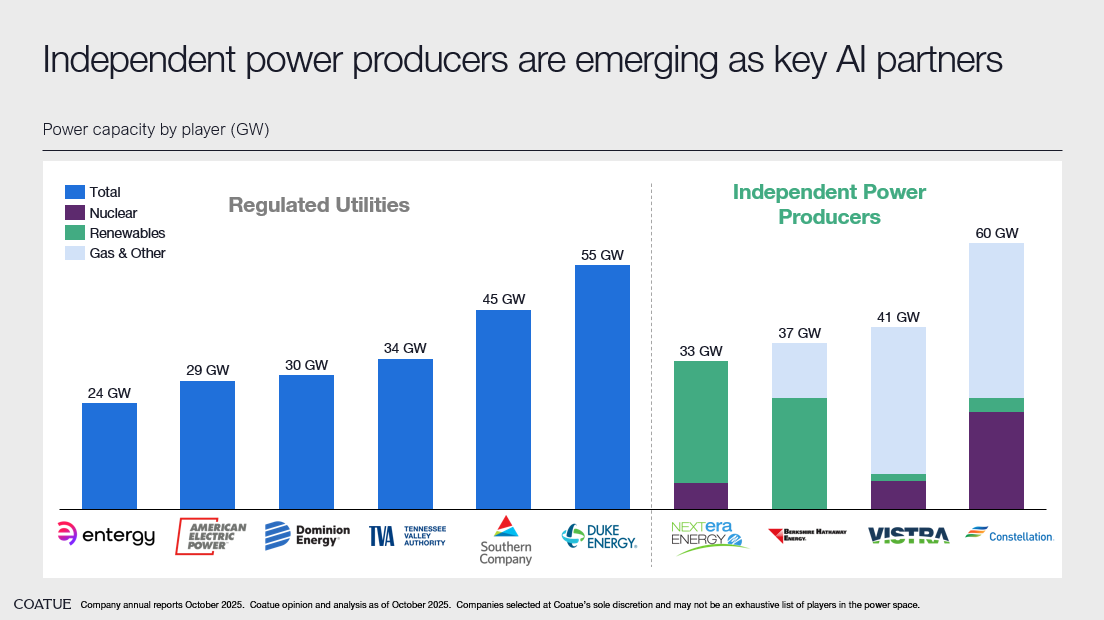

If that’s right, then in a few years, all these “bring your own energy” producers might be a in a bit of trouble:

Independent power producers are an increasingly popular source of energy for data centers, relative to the traditional grid.

And this doesn’t even include the actual “bring your own power” mini-producers, like Bloom Energy.

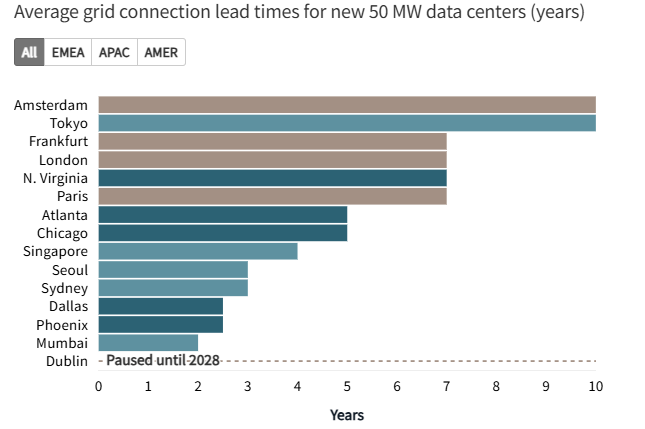

Again, I don’t really know what to make of all this, but getting power, does appear to be a bottleneck:

Average lead times for Data Center grid connections range from 2 years to never (in the case of Dublin).

Even the relatively civilized Dallas has a 2.5 year lead time before a new data center can expect any power. Amsterdam and Tokyo? Come back in a decade. Dublin? Gone fishin’.

6. Clean Coal

A bonus chart because it’s tragically amusing, and well, topical.

It’s cold in the northeast, and because our fearless leaders were very insistent that we banish natural gas because of the environment, we now get warmth from an old friend:

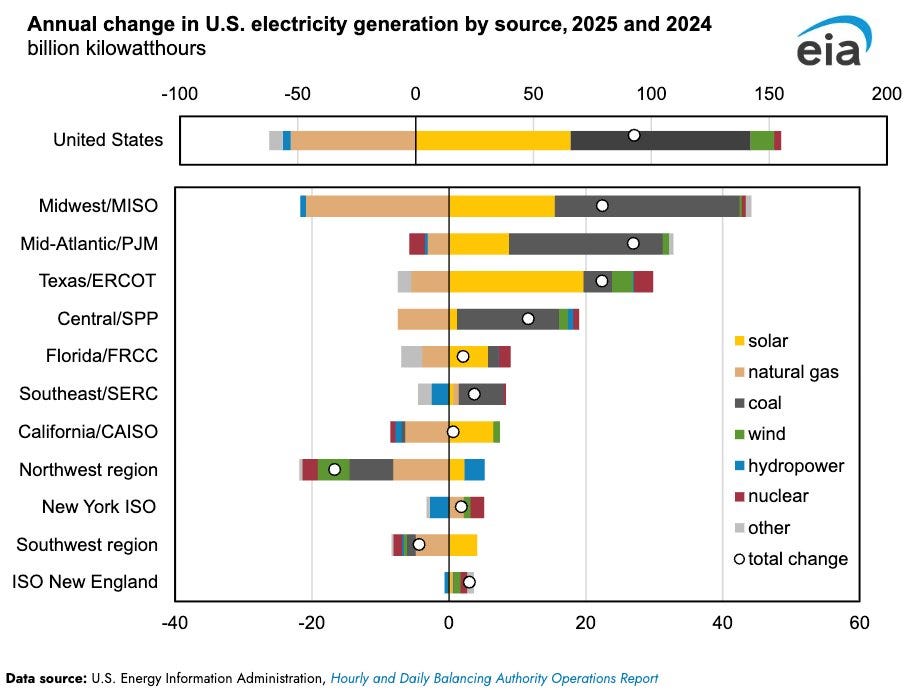

Coal has been the leading source of new energy generation in the Midwest and the Mid-Atlantic over the past two years.

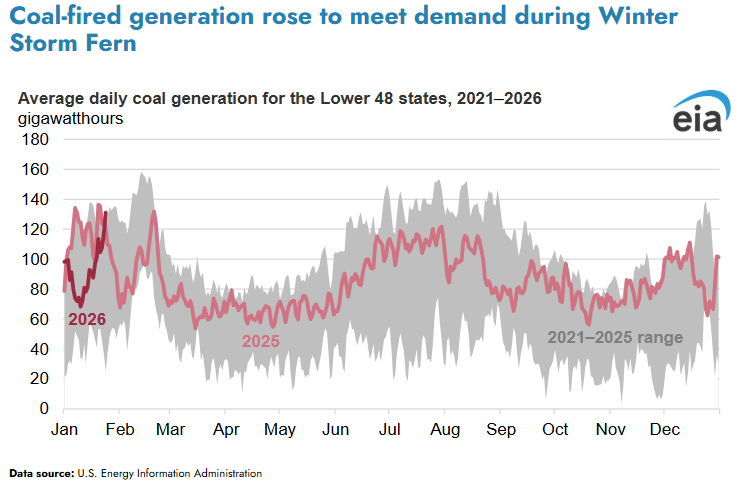

During the most recent storm, it was Coal that rose to the challenge:

In the week ending January 25, 2026 [of Winter Storm Fern] . . . coal-fired electricity generation in the Lower 48 states increased 31% from the previous week . . . natural gas generation in the Lower 48 states increased 14% from the previous week while generation from solar, wind, and hydropower declined. Nuclear generation was nearly unchanged.

And in the absence of coal, well, there’s always good old petroleum oil:

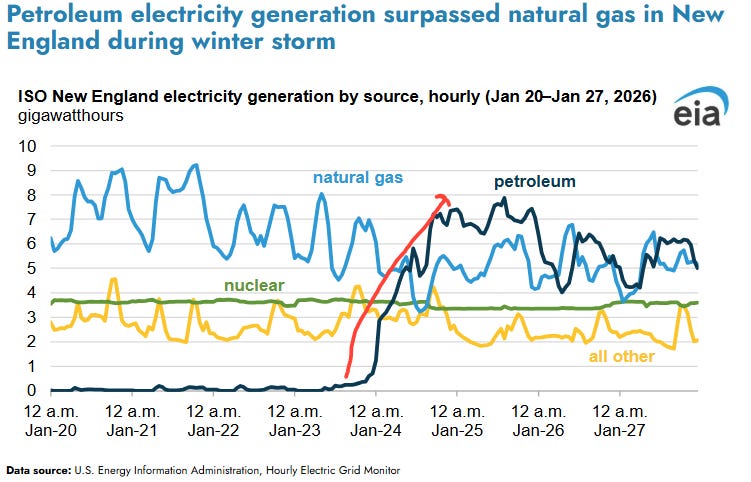

When Winter Storm Fern affected New England this week, petroleum was the predominant energy source starting around midday on January 24 and lasting until early morning on January 26. Since then, petroleum and natural gas have been fluctuating as the primary energy source.

Coal and Oil are so back. Good work, team.

Previously, on Random Walk

Private Credit and Insurance, two peas in a pod (reprise), and a chart dump on default rates

five charts on the rise of private credit in life insurance

Energy in 1776

It’s July 4th, so Happy Birthday America, and we’re going to keep it light and only semi-topical.

Random Walk is an idea company dedicated to the discovery of idea alpha. Find differentiated data, perspectives and people, and keep your information mix lively. A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds. Fight the Great Idea Stagnation. Join Random Walk. Follow me on twitter. Follow me on substack: